Designing Emerging Technologies in 2026

Emerging tech is not a form-factor problem. In 2026, we need to design emerging technologies that look beyond techno-centric appliances.

The modern tech discourse is muddled with buzzword technologies being referred to as emerging technologies, collectively. So much so that when we think of emerging technologies, we fail to look beyond things like AR Glasses, Mixed Reality Headsets, or more recently "AI hardware" or "Agentic AI".

But that's not the limit of Emerging Tech Design. In fact, Designing yet another "AI hardware" or somewhat better "AR Glasses" completely misses the point of designing emerging technologies.

The Form Fallacy

Here's the harsh reality, a new form-factor isn't going to make AI hardware suddenly more useful. Emerging technology design isn't just about giving technology a new kind of input and output interaction.

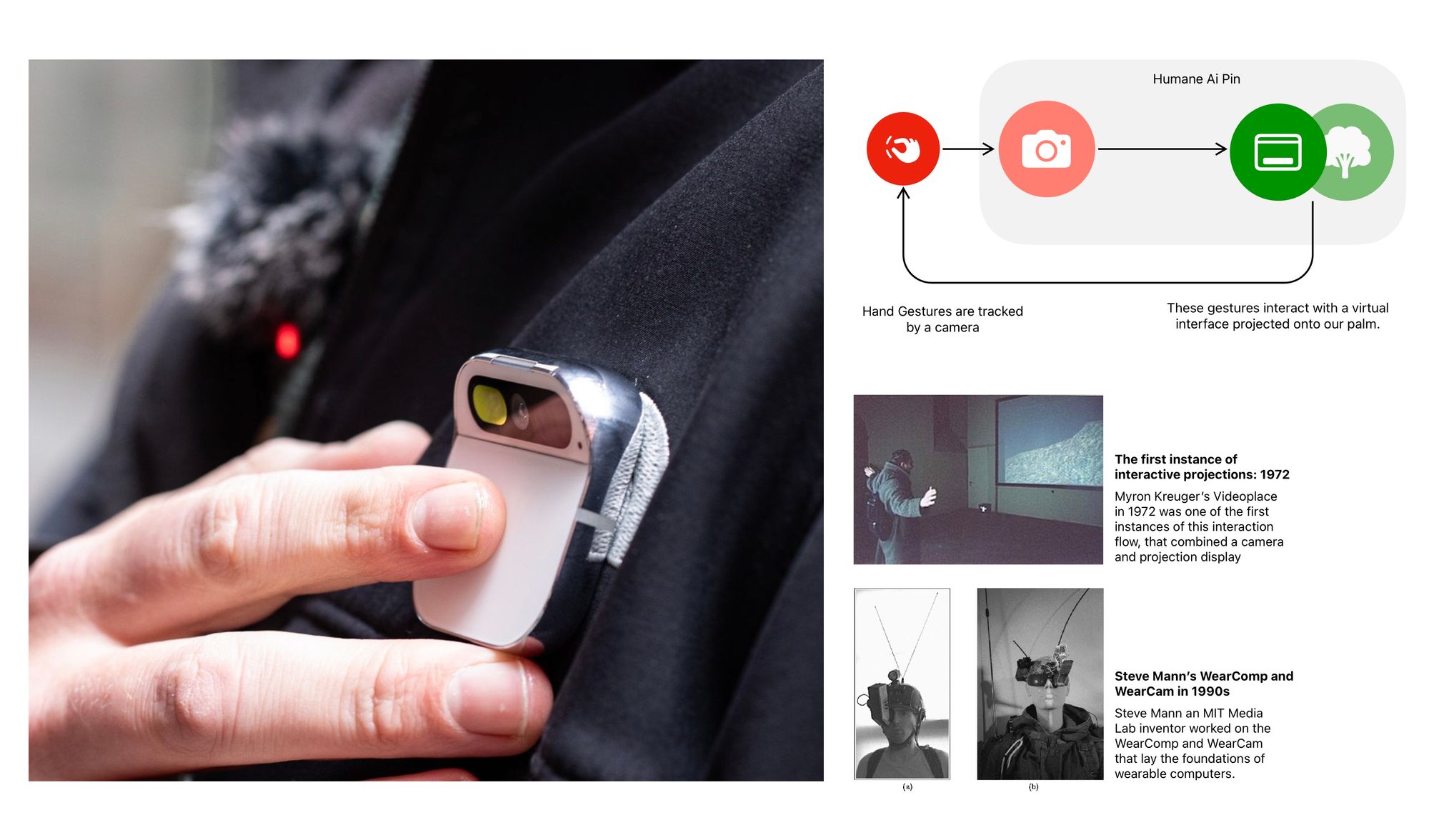

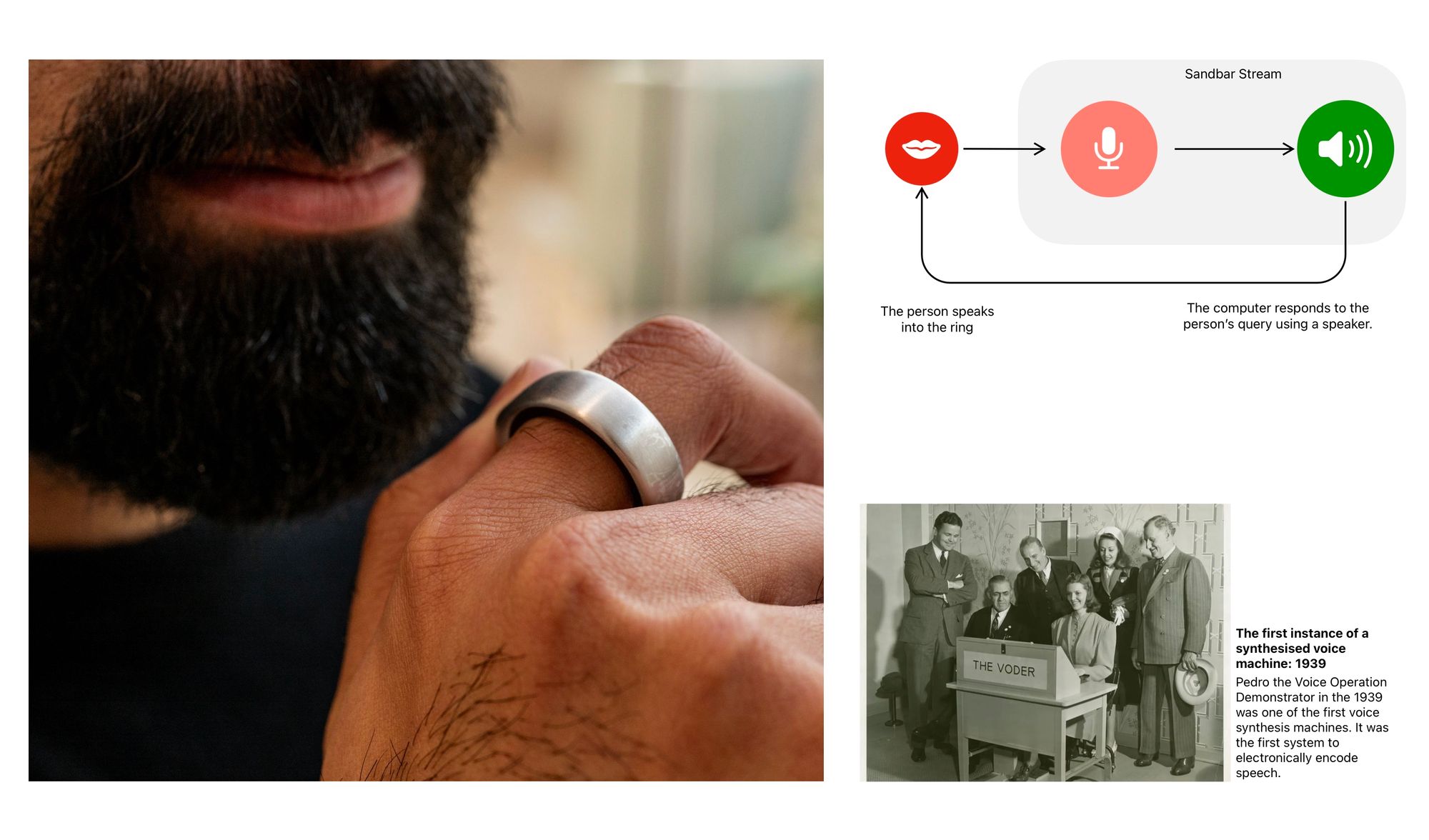

Mixed Reality Headsets, Projection based interfaces, AR Glasses, AI Chatbots, are novel methods of interaction, that combine existing technologies into a sensor—actuator system (or input or output in the case of software) to create a new experience. They are a new form of housing for technology. Making them doesn't automatically make them desirable to people.

The Vision Pro presents a vision of spatial computing but fails to provide people a reason to buy it over a traditional computer. It doesn't really solve a pressing need in people's lives.

The Ai Pin failed, not because the form factor wasn't ideal, it failed because the device makers had no idea who their user was and so the product was little more than a string of cool demos at its best.

Emerging Technology is technology being used in a novel way to solve human problems. so that they spark our imagination of a different, better future. What gives them the "emerging" status is the promise of significant changes in people's lives through a new medium.

When the focus is on people and their needs, it seems counter intuitive to begin by wrapping a new technology in hardware. To reach a form, one must go through the process of designing it.

To design something you must know who you are designing for, and what is the problem to solve, before you can really finalize a form.

The Design Process

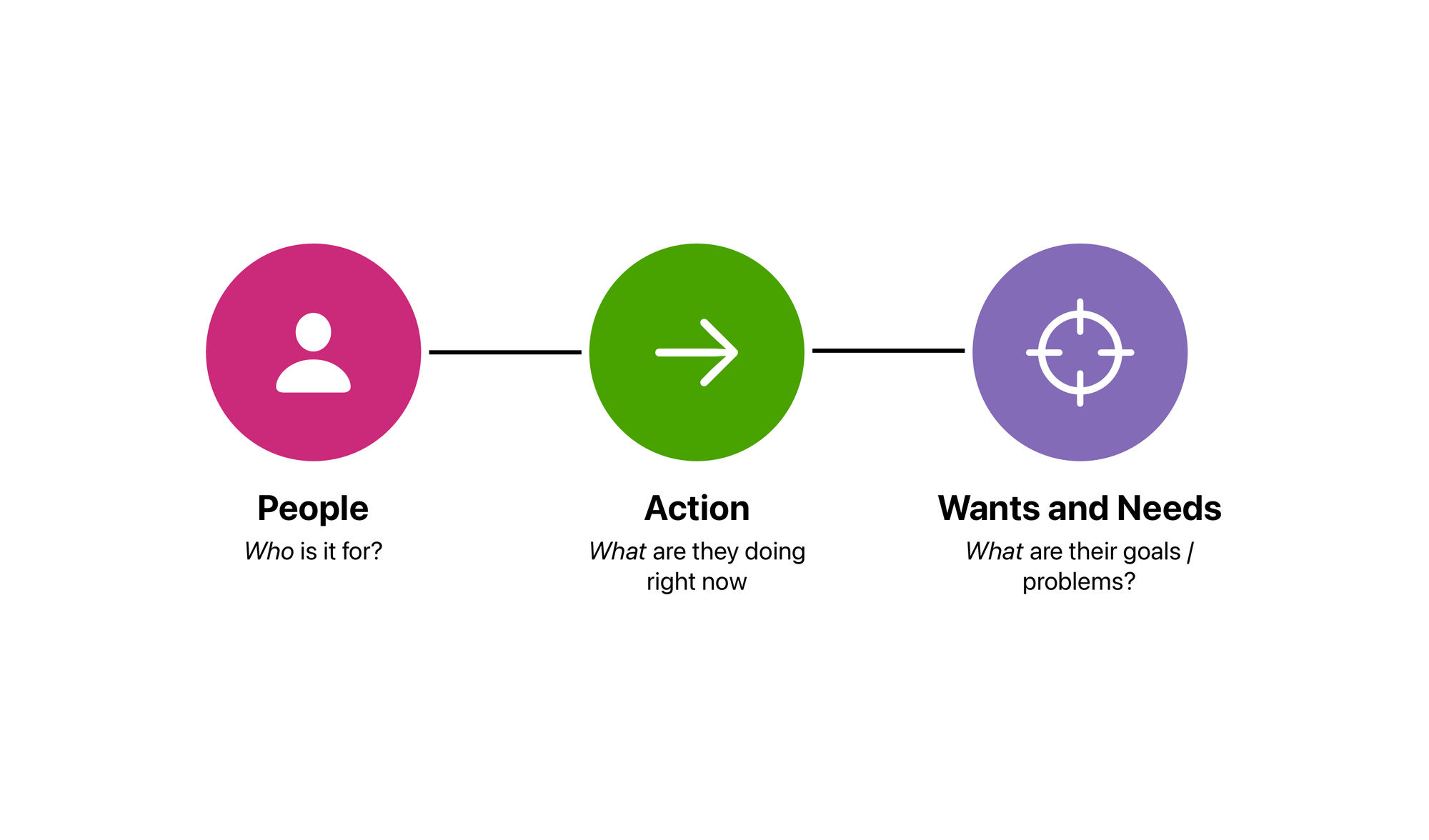

We start with the people, their wants and needs (the problems they are facing) and the actions they perform to achieve them.

The Form Smart Swim Goggles are the perfect example of how emerging technologies like AR prove to be useful when starting with a very clear user (swimmers in this case) and addressing their problems.

Well, That's simple enough. So why don't we have more products that do this?

The reality is that each intervention results in intended and unintended consequences rather than “solving the problem”.

But before we focus on our intervention creating a feedback loop, let’s take a step back and look at the problem itself, and why trying to solve it is so complicated.

The problem

Our environment, circumstances and experiences shape our wants and needs, which are fulfilled by the appliances around us.

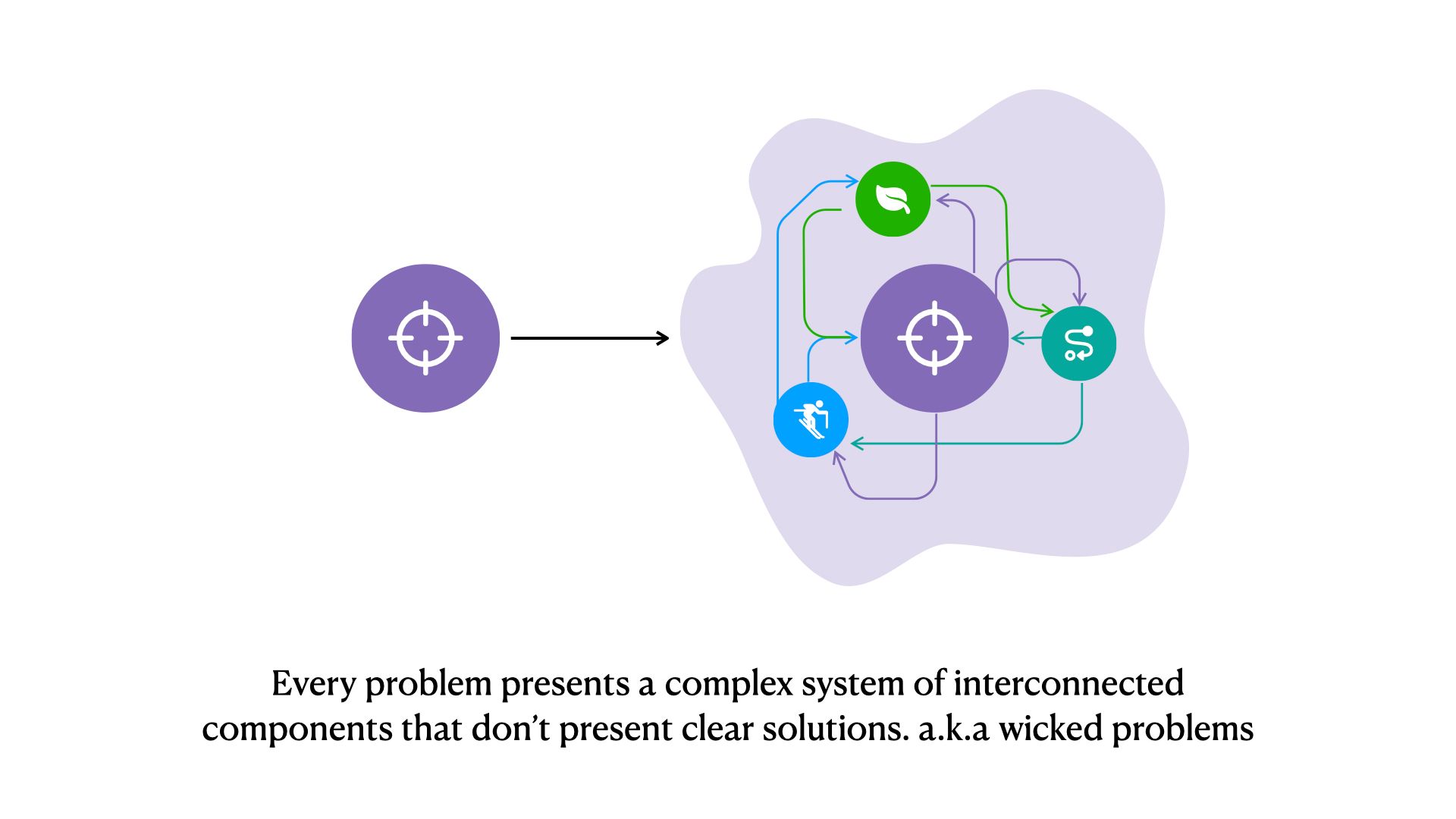

But these wants and needs, or the appliances that are designed to fulfill them don’t live in isolation. They’re part of bigger problems, that are being continually being shaped by our actions, appliances and the world around us.

Each Want and need points to a problem, that problem no matter how straightforward it may seem, is a part of a bigger more wicked problem. How do we tackle them then? It seems as if no new product (or emerging technology) is good enough at solving these seemingly untamable problems?

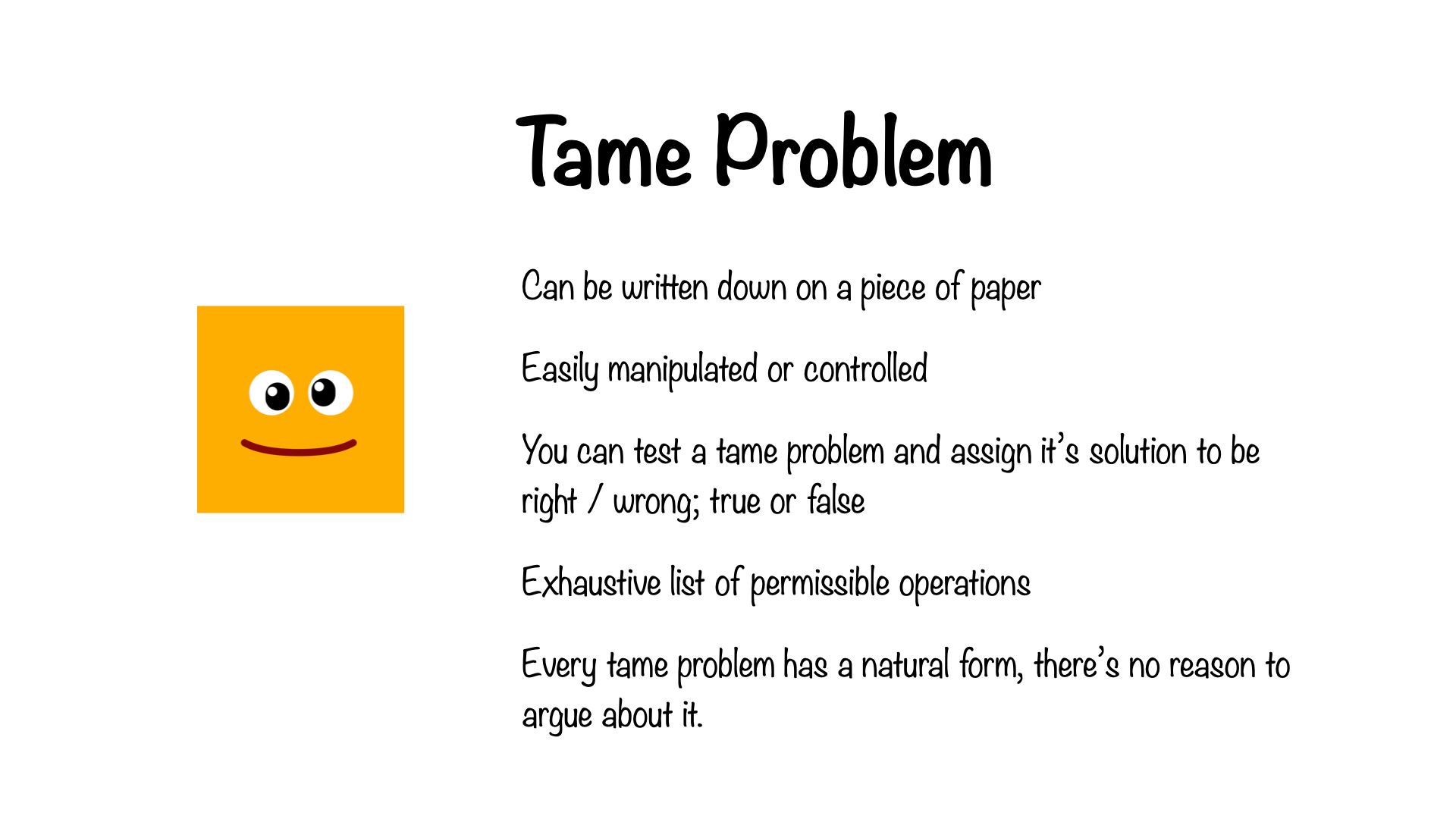

A quick primer on Tame and Wicked Problems.

There are no Tame Problems, Every tame problem lives inside a bigger wicked problem. To tackle a wicked problem, we slice it into smaller, somewhat tamable problems.

A Thin Slice of a bigger problem

Now that we’ve scoped out our problem. Let’s descope again. This time, by creating thin slices of the wicked problem. Identifying people, their immediate issues and how they connect to the bigger problems.

Once we have scoped out our problem as a complex system of elements and interconnected relationships, we find boundary objects to define the bounds of the thin slice of the problem we want to tackle.

With this thin slice defined. We must start our usual design loop. Person, Action, Goal, defines the solution we’re working.

Once we have a fair idea of the people, their actions and their goals. Each task can be divided into input information, the logic, and output logic. This forms the “How” of how a problem is solved.

Once clearly defined we have a good blue print for what we need to design our emerging technology interventions for. The goal of the intervention should be to better help people achieve their goals. Just like a scissor helps people cut paper, or eyeglasses help people see.

The Interventions

But how do we design the tools that perform the action? How do we design the “emerging technology”. There are many different ways of going about it. I would like to restrict today’s discussion to three methods.

- Creating what's possible and practical for today

- Vision Driven Design

- Creating a speculative future

Creating what's most possible and practical for today

Time Frame: 1-5 years

The best approach for designing products that will launch on a 1-5 year time scale. They use existing systems to build a new solution.

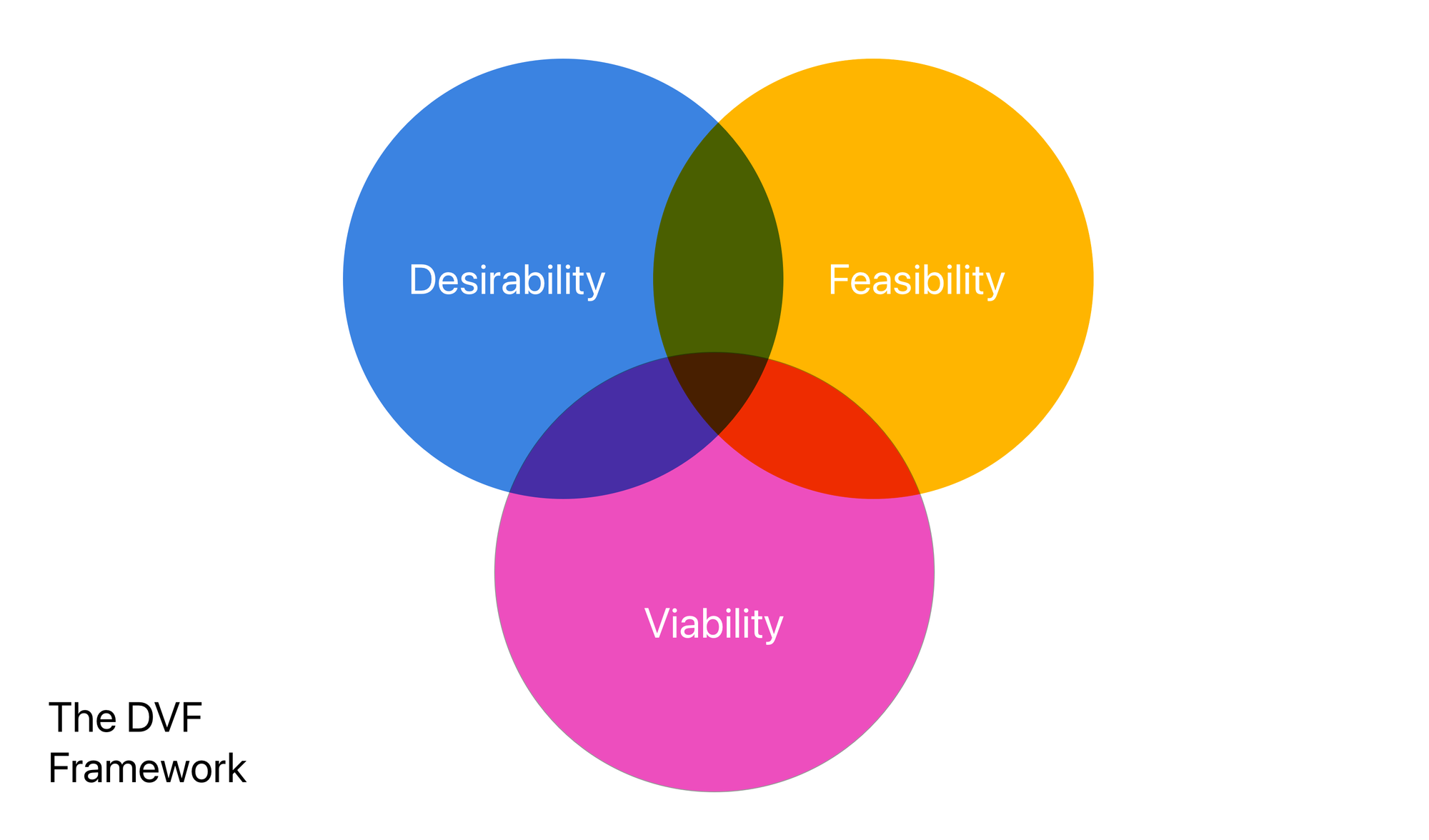

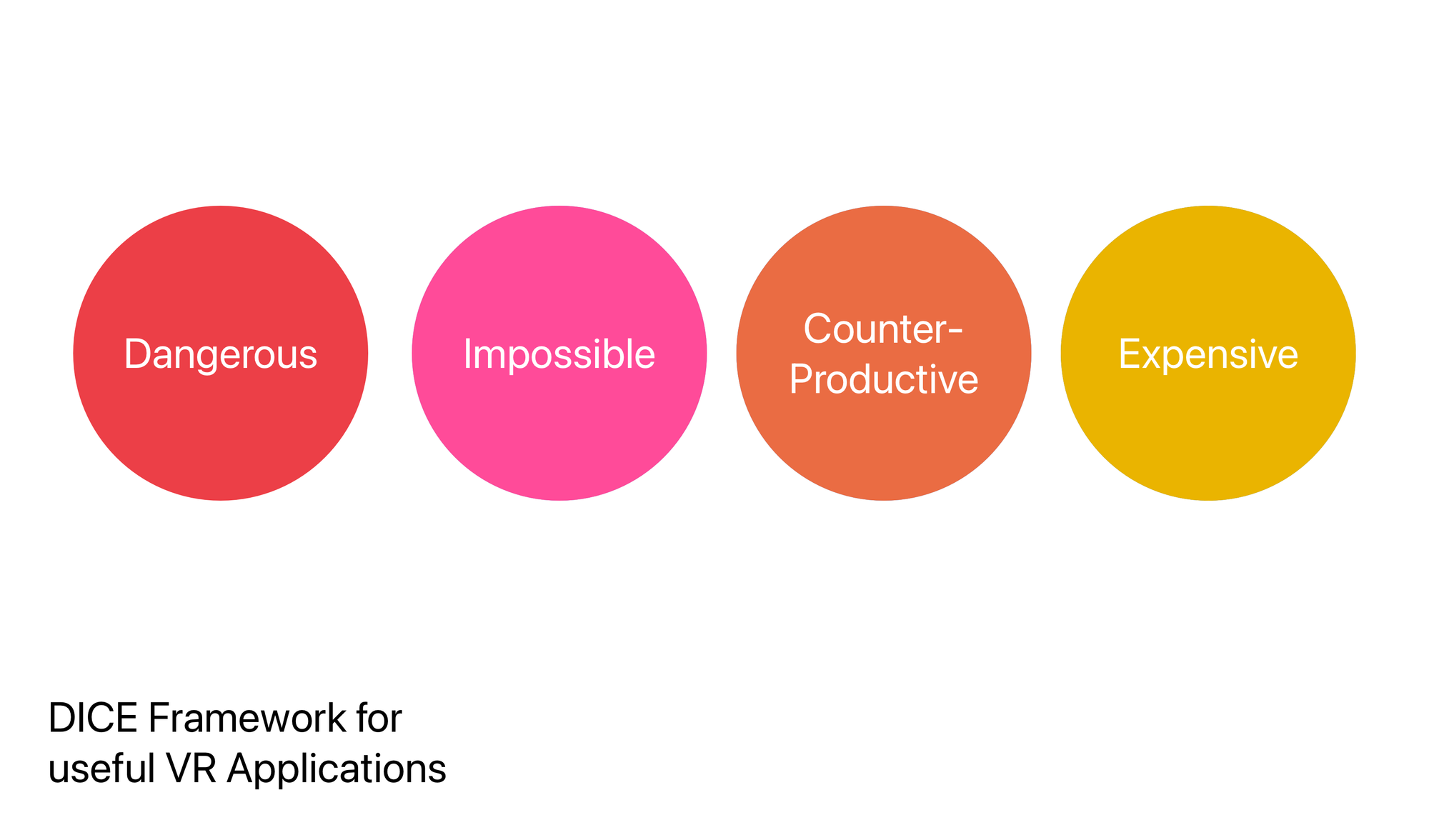

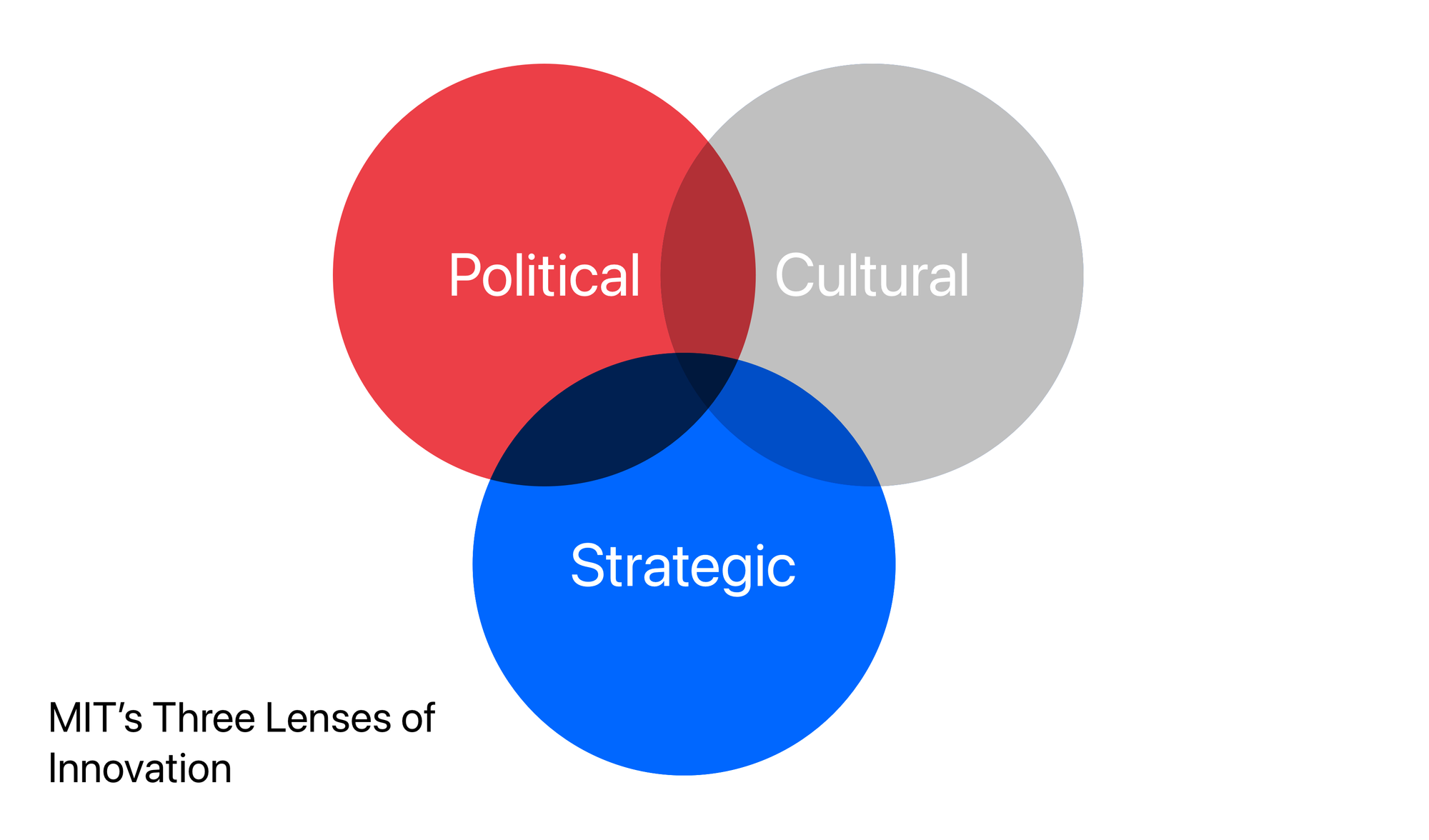

To design products in this space the most practical way to start is to use existing frameworks like the DVF Framework, or the DICE Framework, or MIT Three Lenses of Innovation, amongst many others in order to deeply understand the problem space, and develop a design, tech and marketing strategy.

Remember here you have to ship something quickly, so your prototype solutions must know exactly how something is going to come to life, and how it's going to make money.

The DVF Framework is one of the many frameworks that can be used to identify the who is going to need this product (desirability), how it's going to be built (feasbility), and the financial viability of the product (viability).

The DICE Framework and other similar frameworks are great for applications on pre-defined platforms like VR. They answer the question of "What kinds of applications would be cool for this platform?". In case of the DICE framework, it lays out clearly the kinds of experiences that would be great for VR headsets.

MIT's Three Lenses of Innovation frame the design problem as something that sits in the political, cultural and strategic contexts. It provides an alternative approach to DVF and DICE frameworks.

The Gatorade Sweatpatch is a great example of how to create novel solutions using emerging technologies (micro-fluidics in this case) using existing systems (the patch doesn't require anything but the smartphone!)

Vision Driven Design

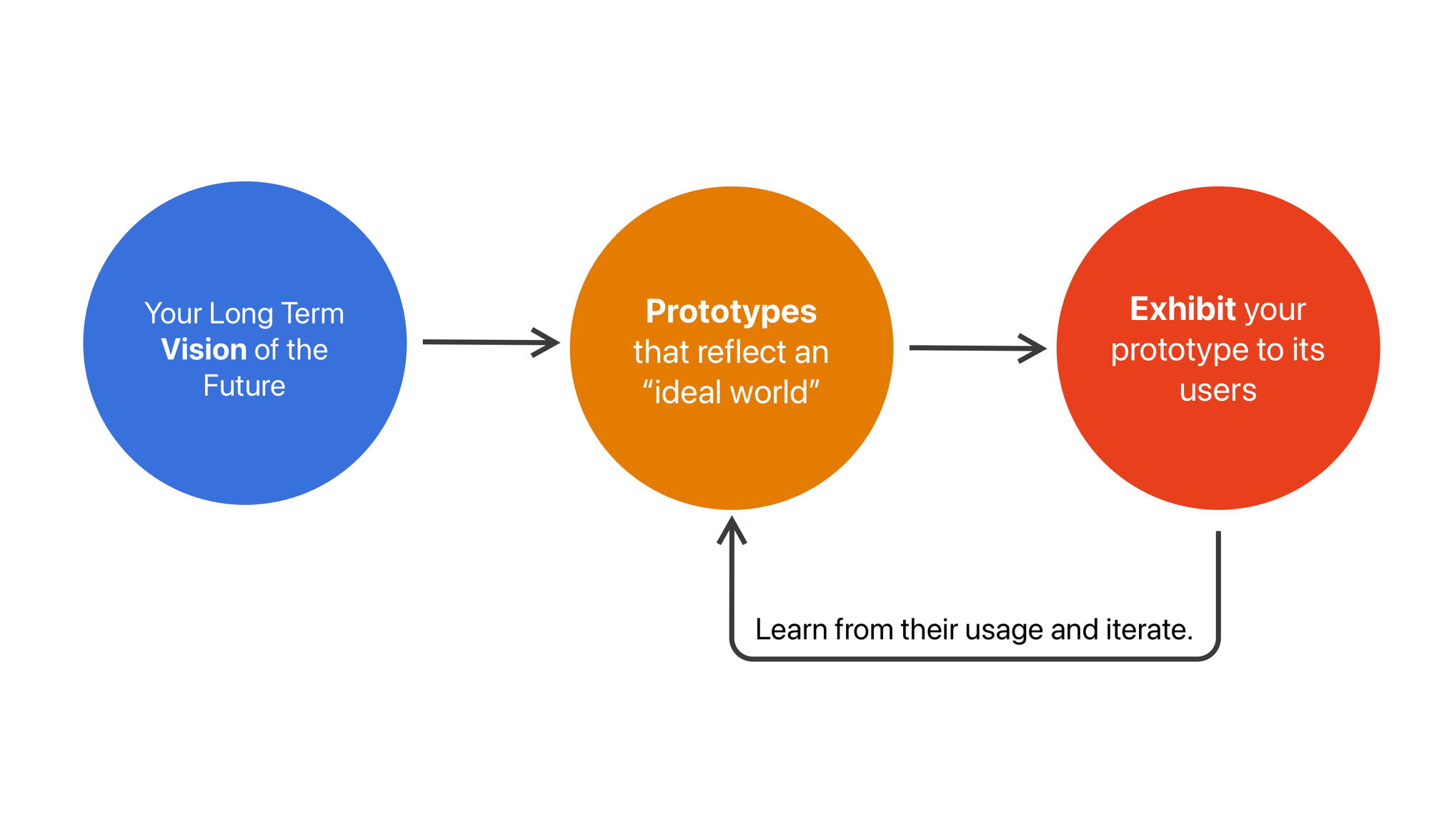

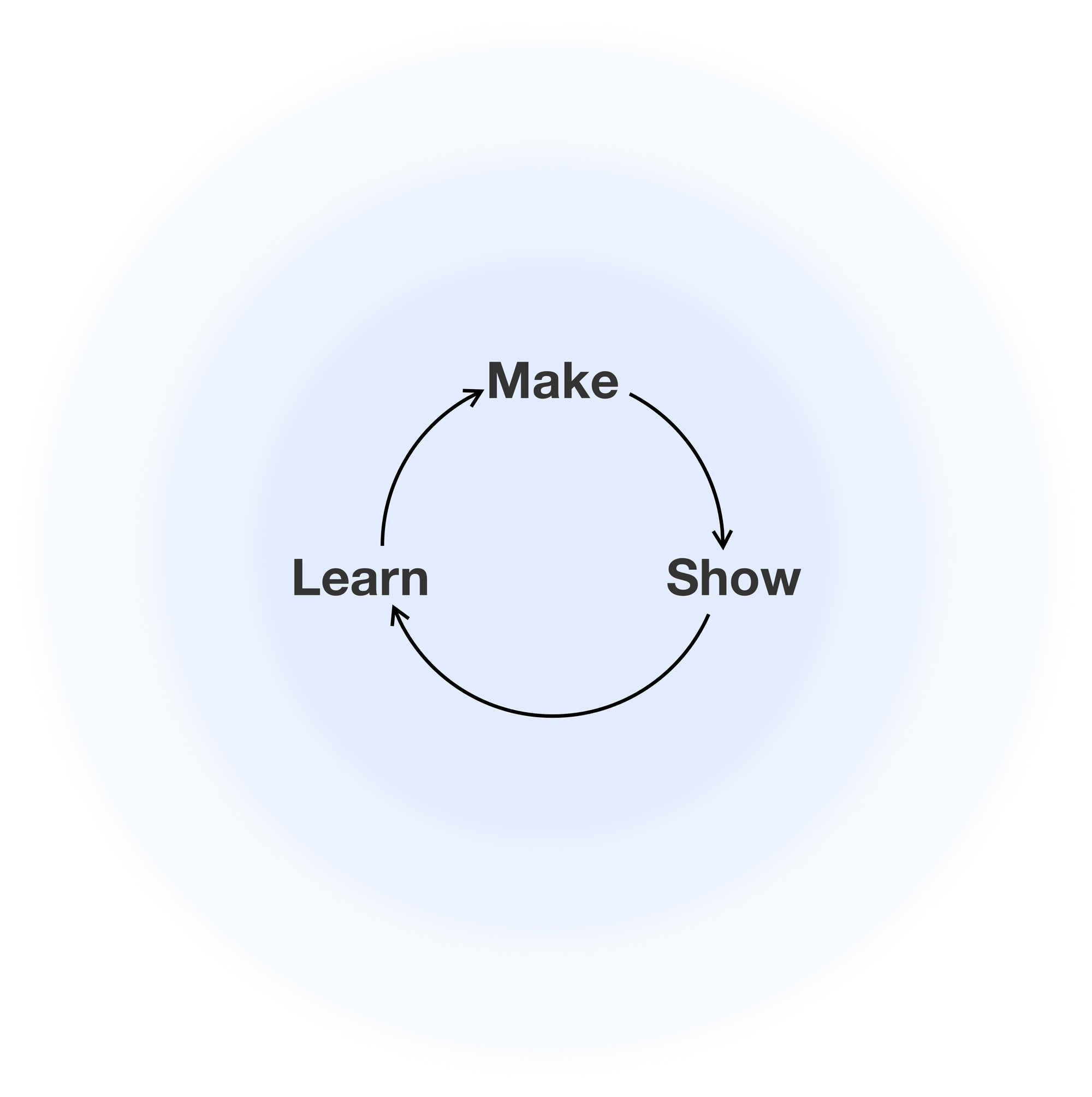

Here designers define a long term vision for how they want to see design in a certain problem space evolve, take a principled stance, build out prototype of their vision, followed by a highly iterative process to reach to a good design.

This is a "making-intensive" and "learning-intensive" process of creating a prototype of the future and tweaking it based on user feedback. It’s driven by a personal vision of how technology should progress (e.g., screen-less computing).

Examples of Vision Driven Design Practices

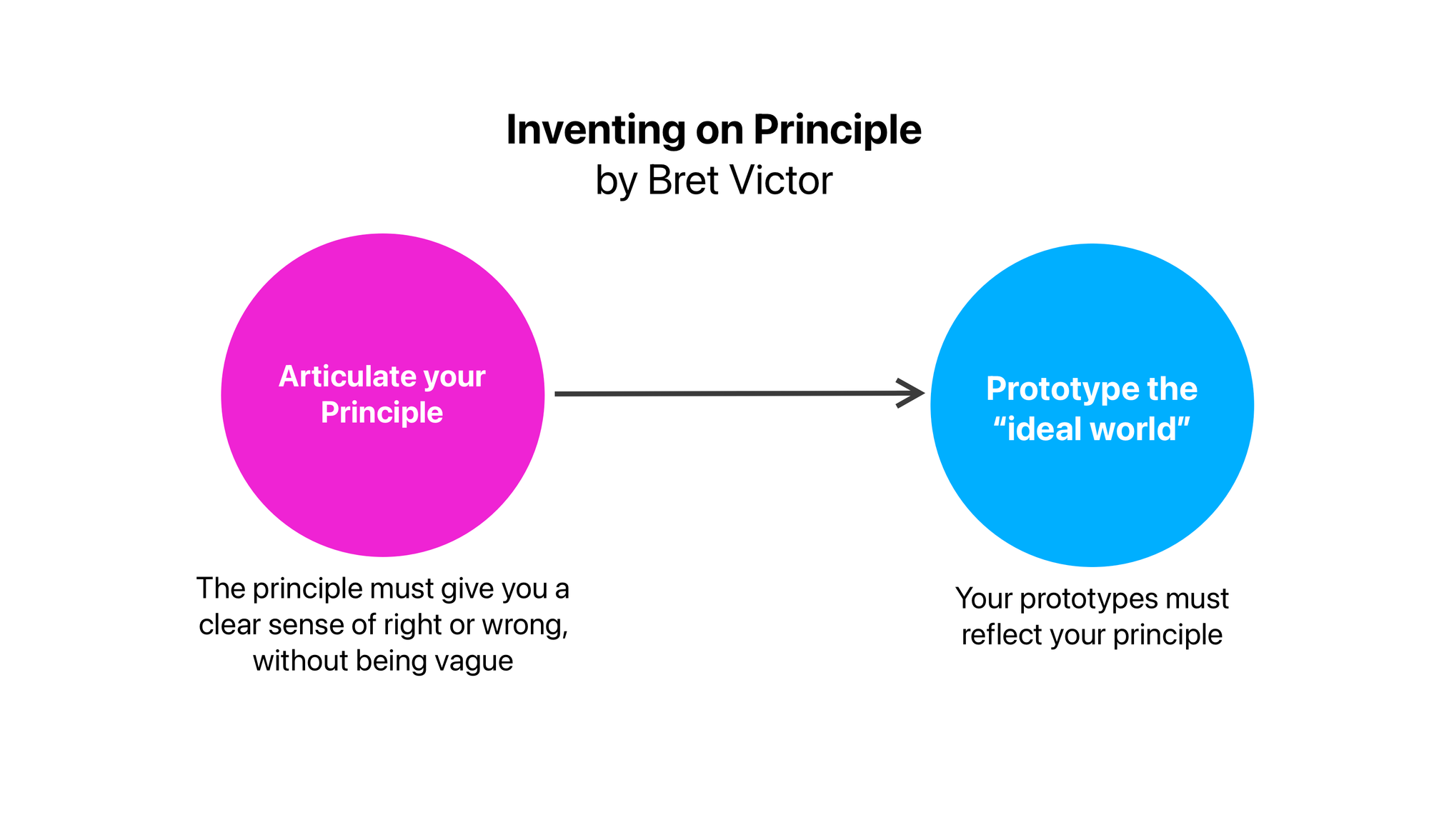

Bret Victor's Inventing on Principle is a similar design practice. Where Victor encourages designers to form a core principle for their work. One that's well articulated with a clear demarcation between right and wrong.

To explain his concept, Bret gives several examples of how inventors have followed a guiding principle to design their ideal world, leading to some profound inventions.

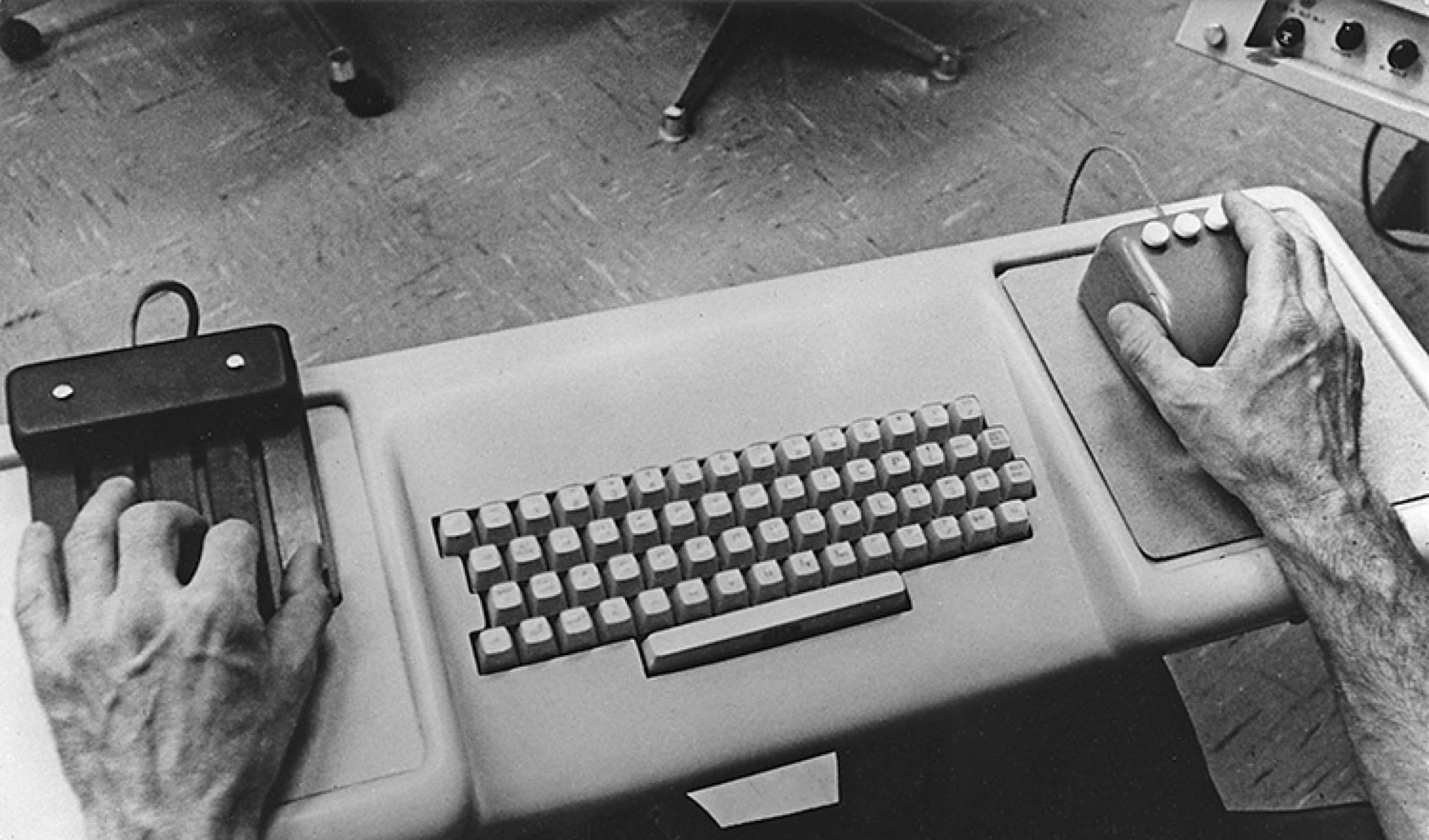

Douglas Engelbart's principle was to augment human intellect, where "knowledge workers" came together to build on each other's collective intelligence. Engelbart invented much of modern computing through this one vision. From Natural Language Search, to the Computer Mouse, to Collaborative Computing.

Alan Kay viewed computers as a medium to "bring new ways of thinking through computers". His work led to the creation of the world's first object oriented programming language, the Dynabook (spiritual predecessor to the iPad), and much more user research at Xerox Parc.

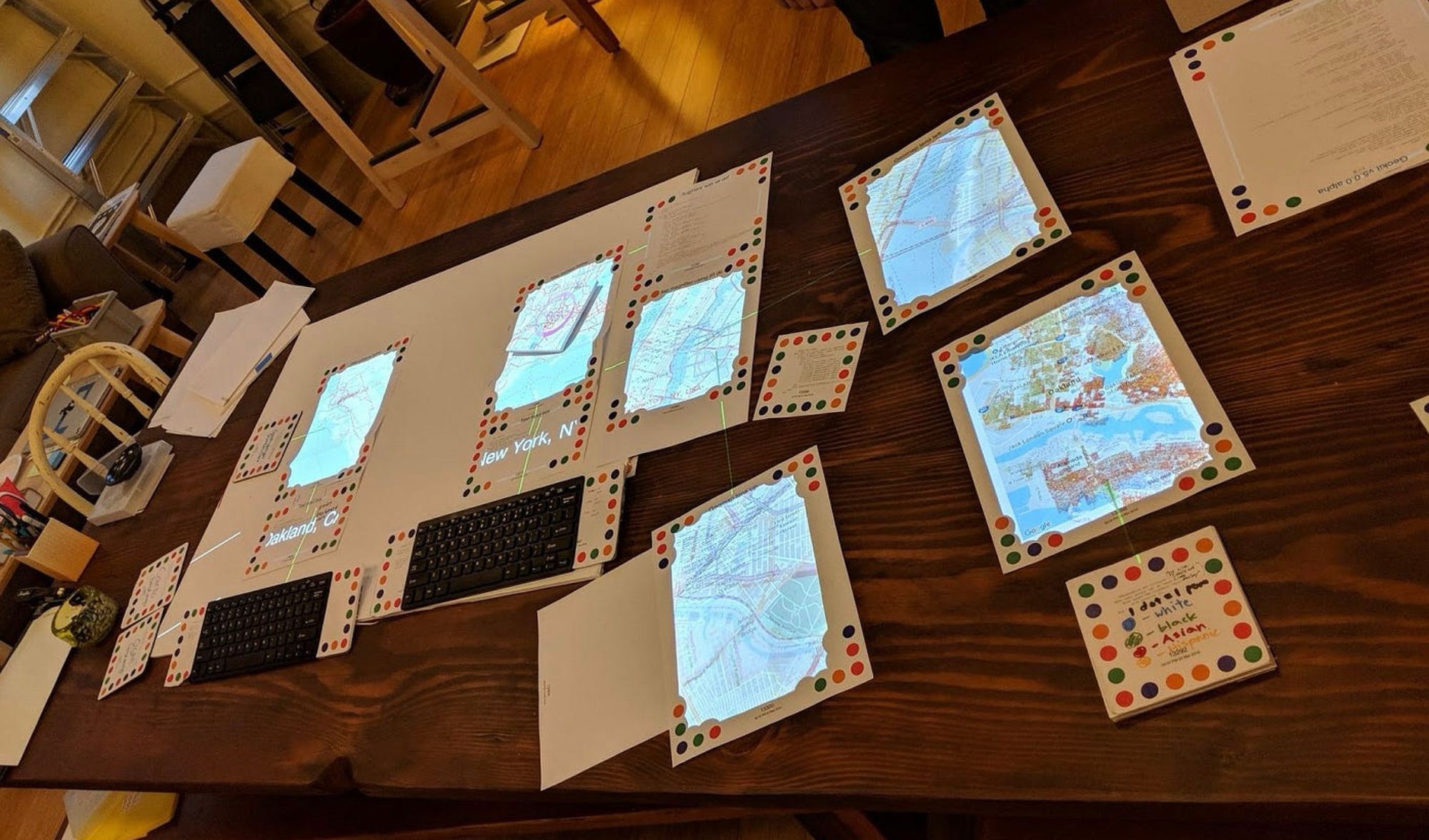

Bret's own principle is that "Creators need an immediate connection to what they're creating" . His work led him to make Dynamicland, a community computer space that enables people to bring and interact with real world objects in a new computing media.

Most Vision Driven Designs fail because there’s obviously a gap between how we imagine things should be and how the things actually end up playing out. That’s inevitable. What's not inevitable is designers through iterative design, designers can tweak their vision and focus to align with what people truly appreciate.

With Vision Based Prototyping, Iteration is the most important step.

It’s in such a space that we get to explore new technologies in unique ways. I personally enjoy this space, as it helps me bring out my ideas in the world.

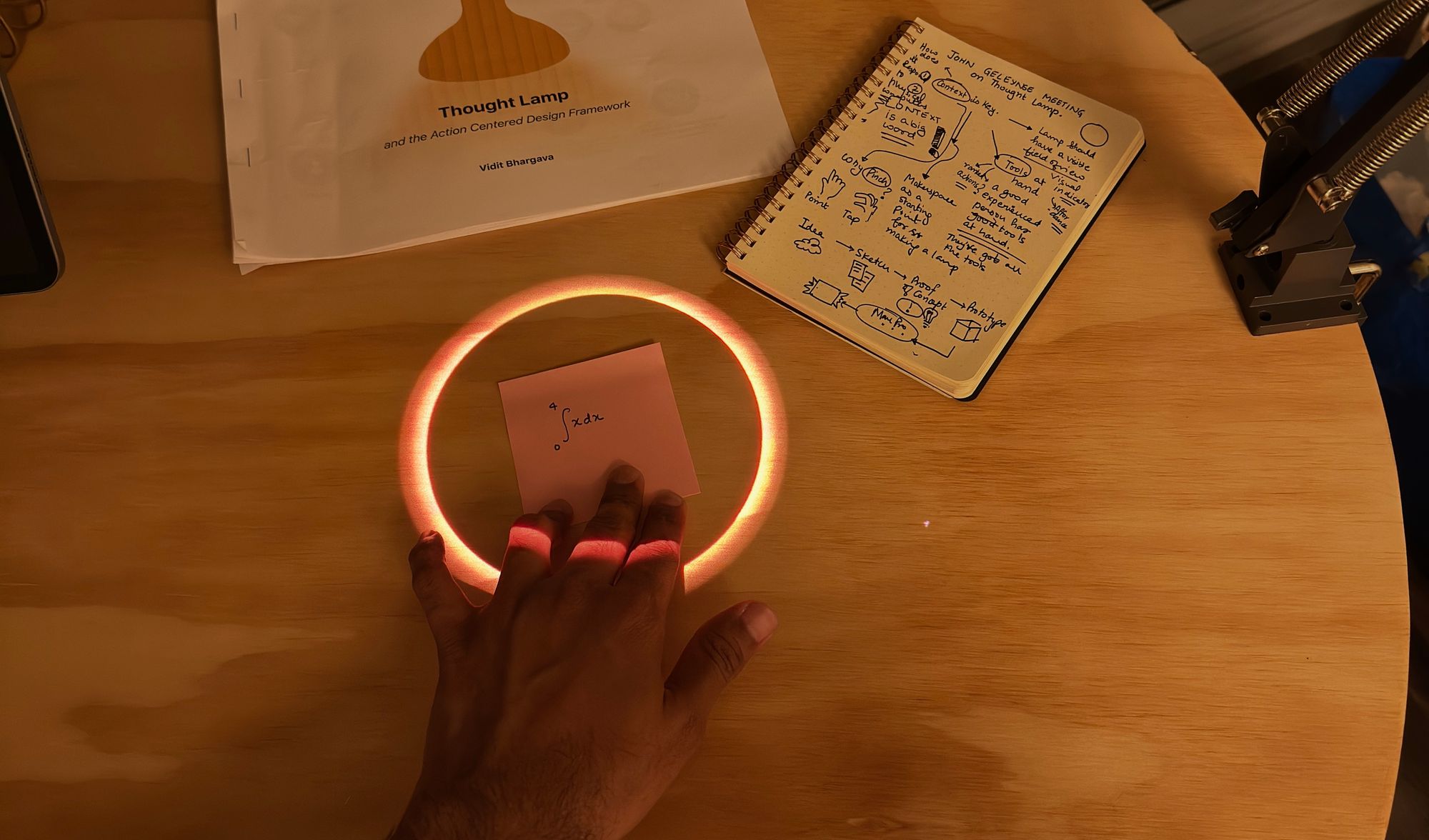

The Thought Lamp is a smart lamp, that acts as a student's ambient study companion. It's a computer that's only present when you need it, and in the background when you don't. It is based on my vision that technology must augment reality, not emulate it, and so it only presents itself when it can augment my reality.

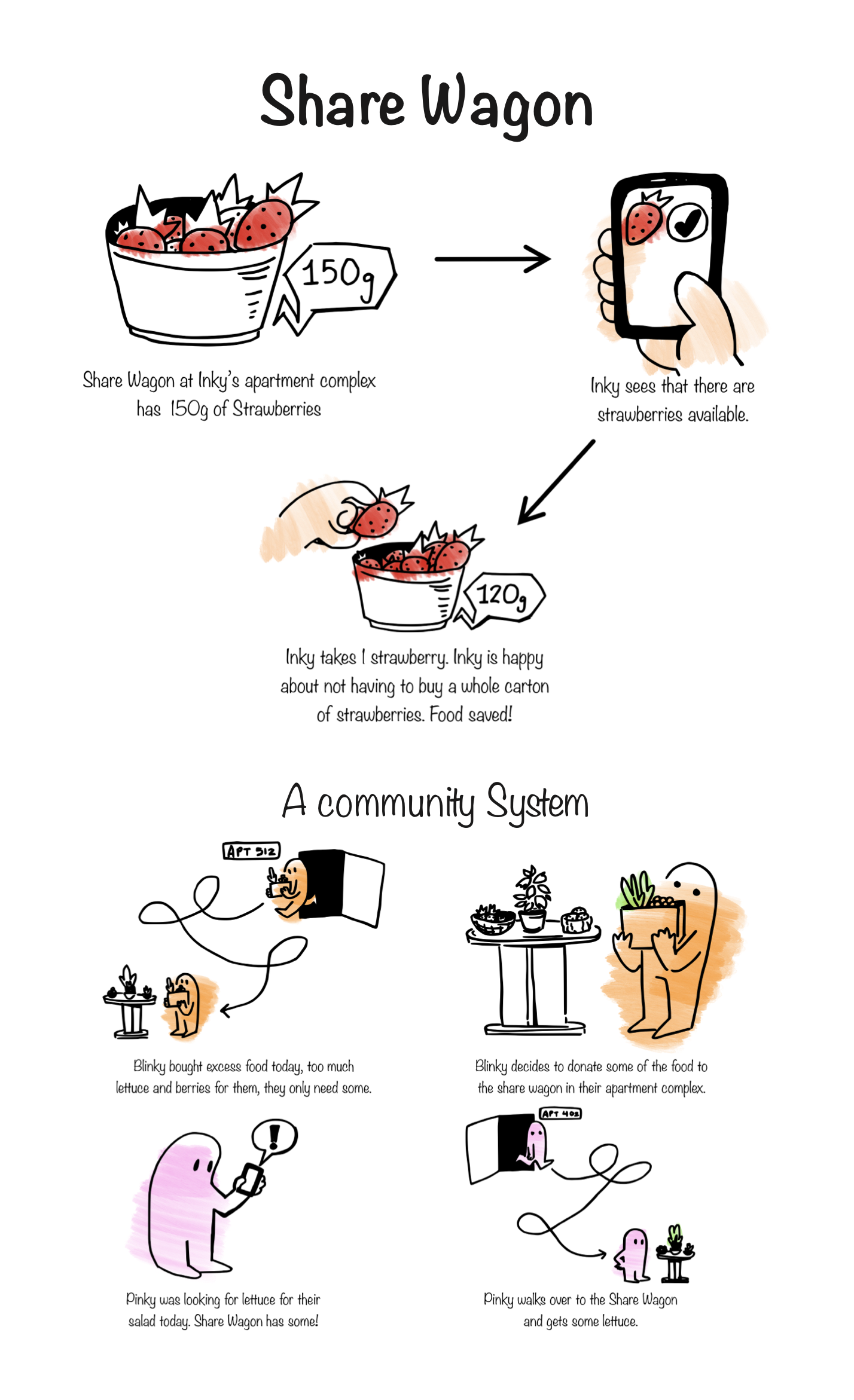

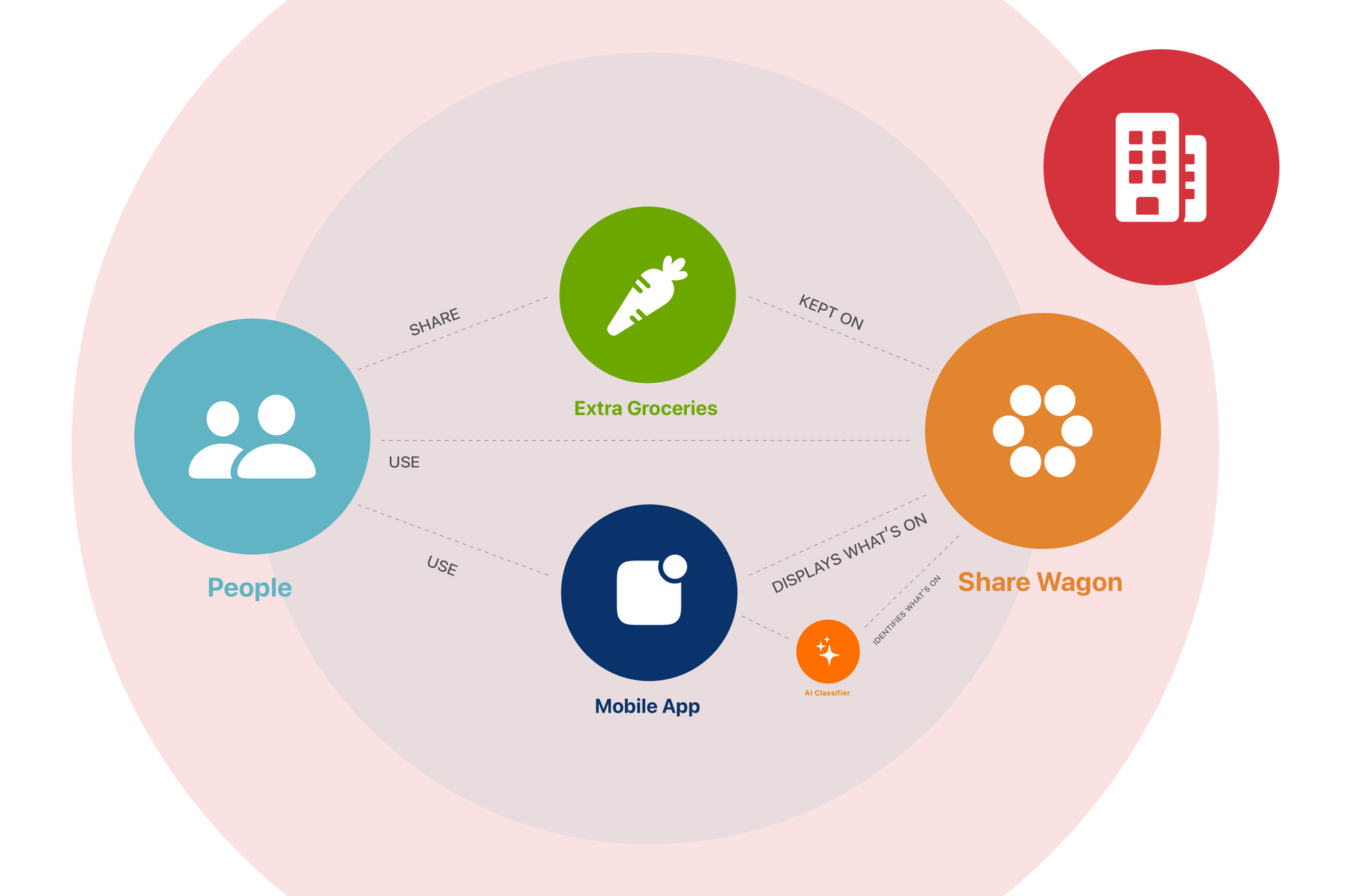

Share Wagon is a community food sharing system, designed to tackle the problem of food waste in apartment complexes. Designed by me and my friend (Aylish Turner), it was based on our collective vision of community building through sharing.

Speculative Design

Time Frame: 50+ years

Speculative Designs are provocations that further the design discourse. This process leads to artifacts that are essential to jog people’s imagination on where the use / misuse of a certain technology might lead us in the distant future. They highlight an urgent need for change, rather than being the change itself.

Very useful if you want to raise awareness for wicked problems not clearly understood by society today.

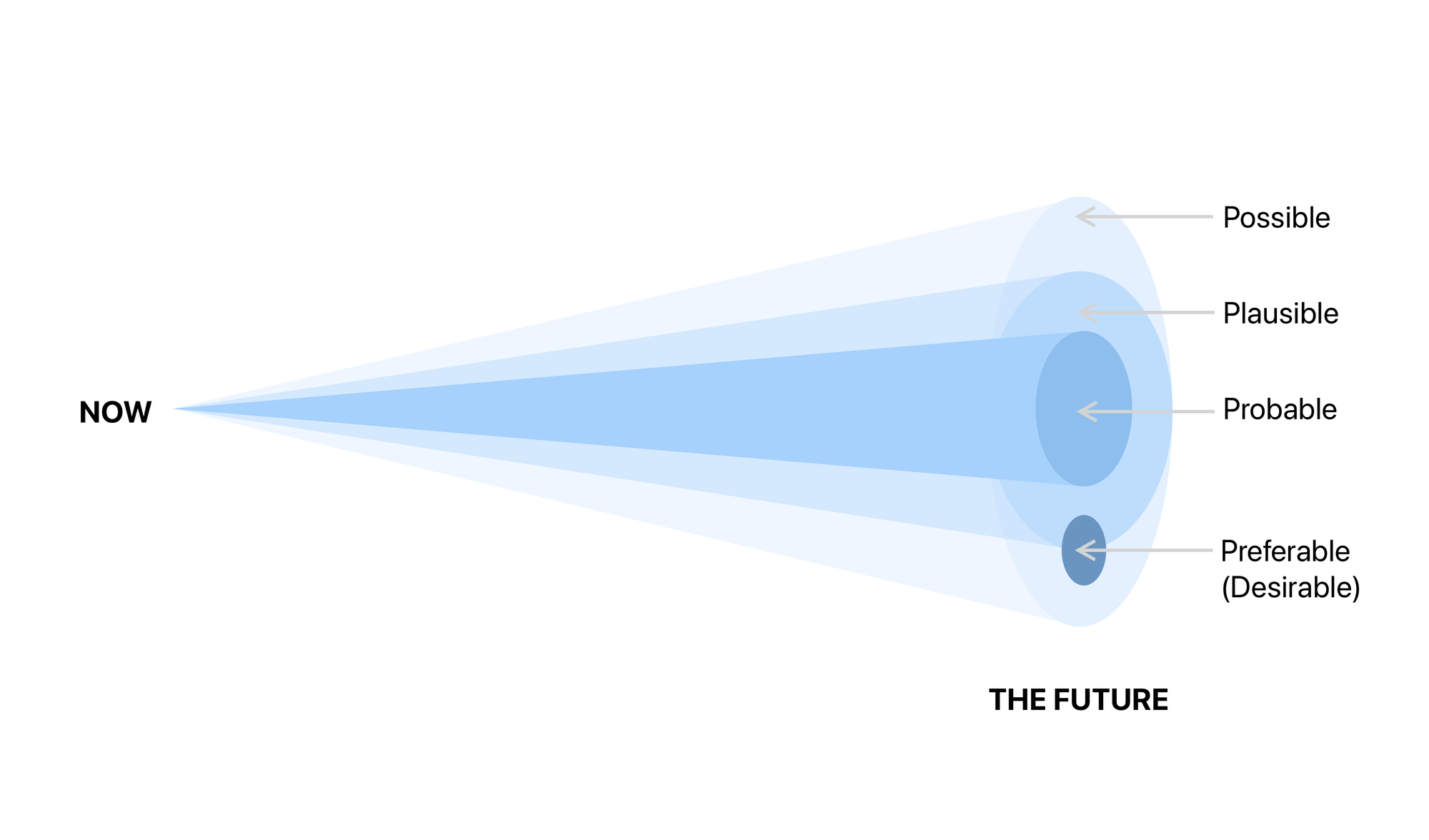

The Future Cone serves as a useful way of looking possible, plausible, probable and preferable futures.

Uninvited Guests (by Superflux) critiques the ubiquity of "smart" appliances, through a day in the life of a 70 year old sometime in the future. The short film through its speculative design and artifacts explores themes of isolation, overuse of technology and a society obsessed with homogeneity and perfection.

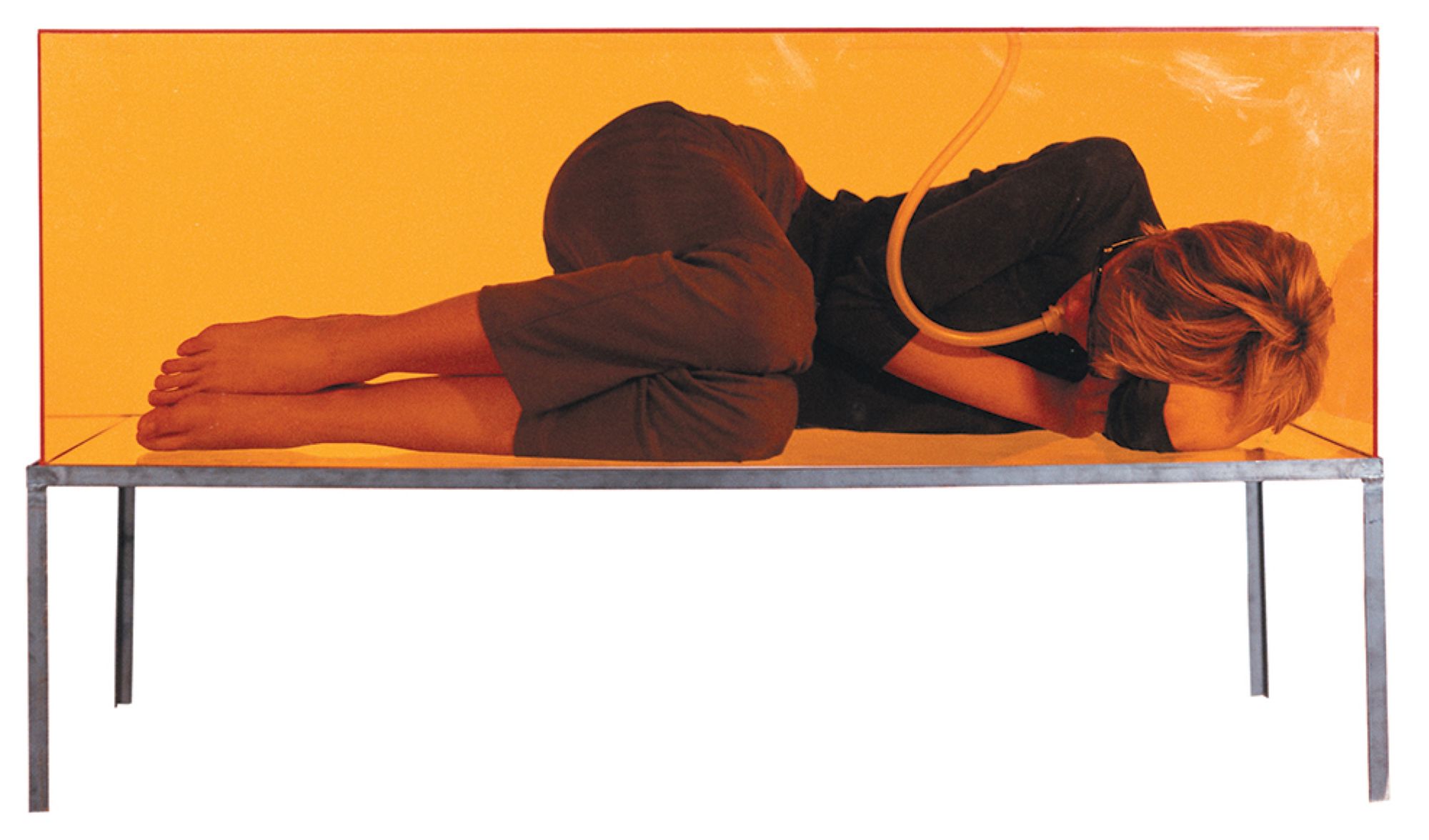

The Faraday Chair (1995, by Dunne and Raby) is a speculative artifact designed as a retreat from all the electromagnetic emissions generated by technology when it eventually becomes ubiquitous. The chair is supposed to give people "psychological comfort by providing sanctuary".

While the idea of a tech detox may not appear to be completely speculative today, 30 years ago, this was unthinkable, and the strong, provocative visuals sparked curiousity and interest in the matter.

We have an artifact that solves a clear human need. What next?

Appliances (or tools or design interventions) are great ways to tackle small challenges. As we've seen through our process. A toaster is great solving for the need to have fresh toast at breakfast, but not much beyond that.

Remember, we started with a bigger problem, and de-scoped it into a very thin slice? So we've really just solved for a very small and specific need. The bigger problem is still largely unsolved.

We’ve solved a thin slice, what about the rest of the slices? We can take two different approaches here.

First, Product Growth (Vertical Integration) we increase our slice of the problem space and continue to grow infinitely. We grow our tool to encompass more problems and gradually get a bigger slice of the pie. Most traditional products have worked this way.

The problem with this approach is, unintended consequences add up as the product grows and result in adjacent wicked problems. For example the proliferation of the smartphone as one device to for all our computing needs has resulted in the adjacent issue of it amplifying loneliness and isolation through addictive apps.

Platforms, Protocols and Systems (Horizontal Scaling)

The second approach is, we acknowledge there’s only so much a product can grow until it becomes bloated and dishonest to its original purpose.

And we create a system that allows other slices to interact with our solution. Creating a fully formed puzzle where everyone comes together to solve the problem. The solution space still continues to grow, except this time, one company doesn’t have to do it all.

We create a platform and frameworks that enable more people to hook into our intervention and build out. Thereby delegating the process of tackling a wicked people to like minded people.

Tools that allow hooks into other solutions become platforms rather than appliances.

And before you know, your emerging technology product is not an appliance, it’s a platform that talks to and helps other talk to it to solve bigger problems.

Examples of systems

Remember the Gatorade Sweat Patch? It's not just a one-off product. It's part of the bigger Gatorade System that enables athletes to monitor their fitness.

The Gatorade Gx System

The Gatorade Gx is a good example of a vertically integrated system that aims to solve for an athlete's fitness monitoring using a range of low and high tech solutions.

The Lego Smart Play System

The newly introduced Lego Smart Play bricks are a set of primitive tangible technologies like a positioning system, a smart brick that coordinates with minifigures and other nearby objects to enable new experiences.

This is a great example of using emerging technologies. Lego built out a smart brick system to allow kids to have interactive gameplay sessions without looking at their iPad screens, and they didn't just stop at a standalone system, they literally built the building blocks that would enable kids to show their creativity.

IDEO's Food Waste Alliance

When IDEO started tackling food waste a little over 10 years ago, their big epiphany was that food wastage is a far bigger problem than what a single product could solve. So they started building out a system to tackle food waste which led to the Food Waste Alliance.

The iPhone is a case study in emerging tech design

The iPhone is a perfect example of how a product started with immense clarity in who it were serving and what it was solving for, and then quickly expanded into a platform that anyone could build for. Unlocking new possibilities and capabilities that the iPhone excelled in.

The iPhone's biggest strength? Not all apps were made by Apple. In fact, almost all apps on the App Store are made by third party developers. While the iPhone keeps a tight rein on the platform, its platform of Apps might just be the best example of a horizontally scaling system that enabled the iPhone to be so much more than just a touch screen iPod, phone and an internet communicator.

Even in my own explorations of designing emerging technologies, I've tried to go beyond a singular appliance and build out systems or platforms that allow others to adapt it.

The Share Wagon Food Sharing System

The share wagon food sharing system is so simple and straight forward that it can be easily scaled and adopted by anyone willing to set it up in their apartment complex. The core of the idea is to share food with community. Such a system is easily adoptable.

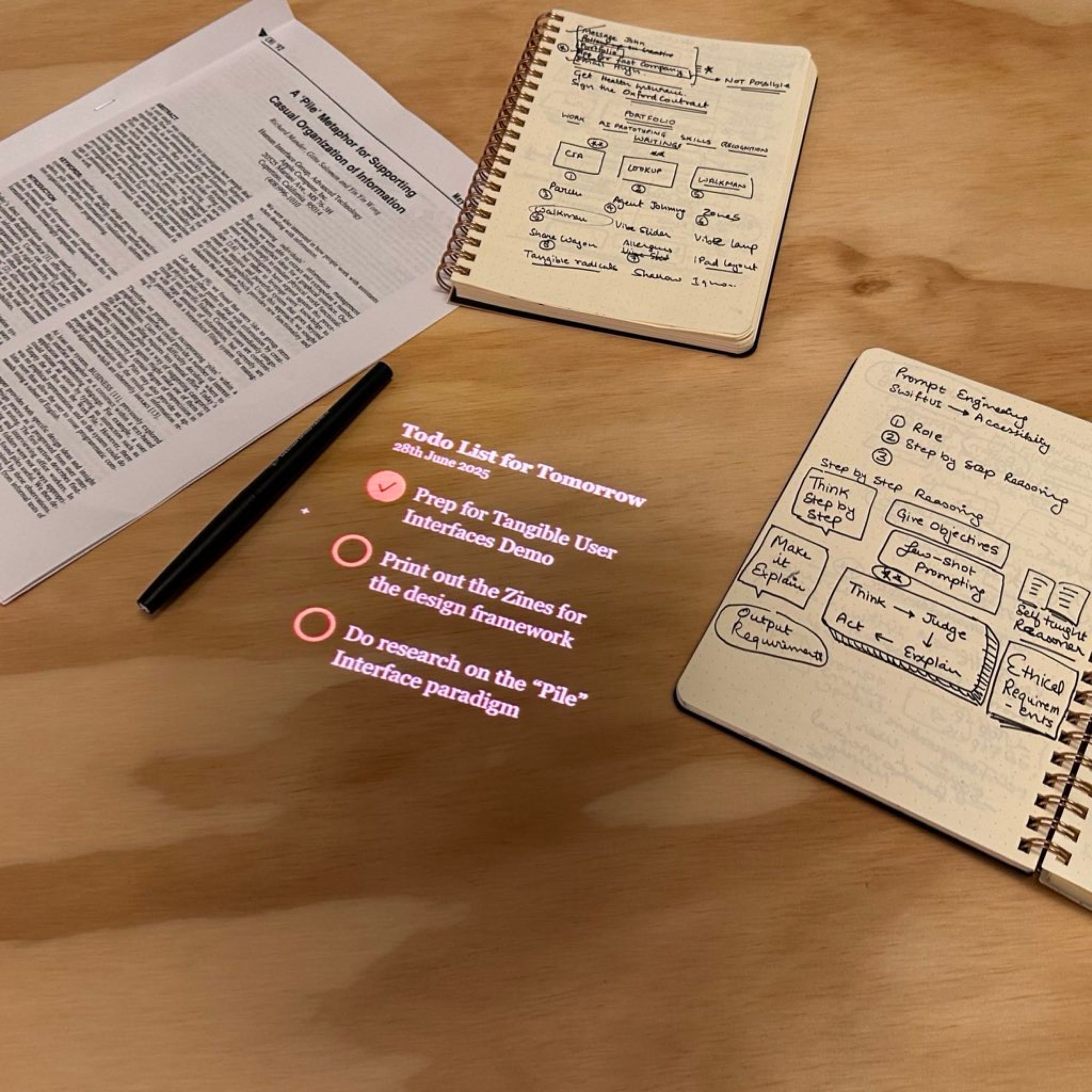

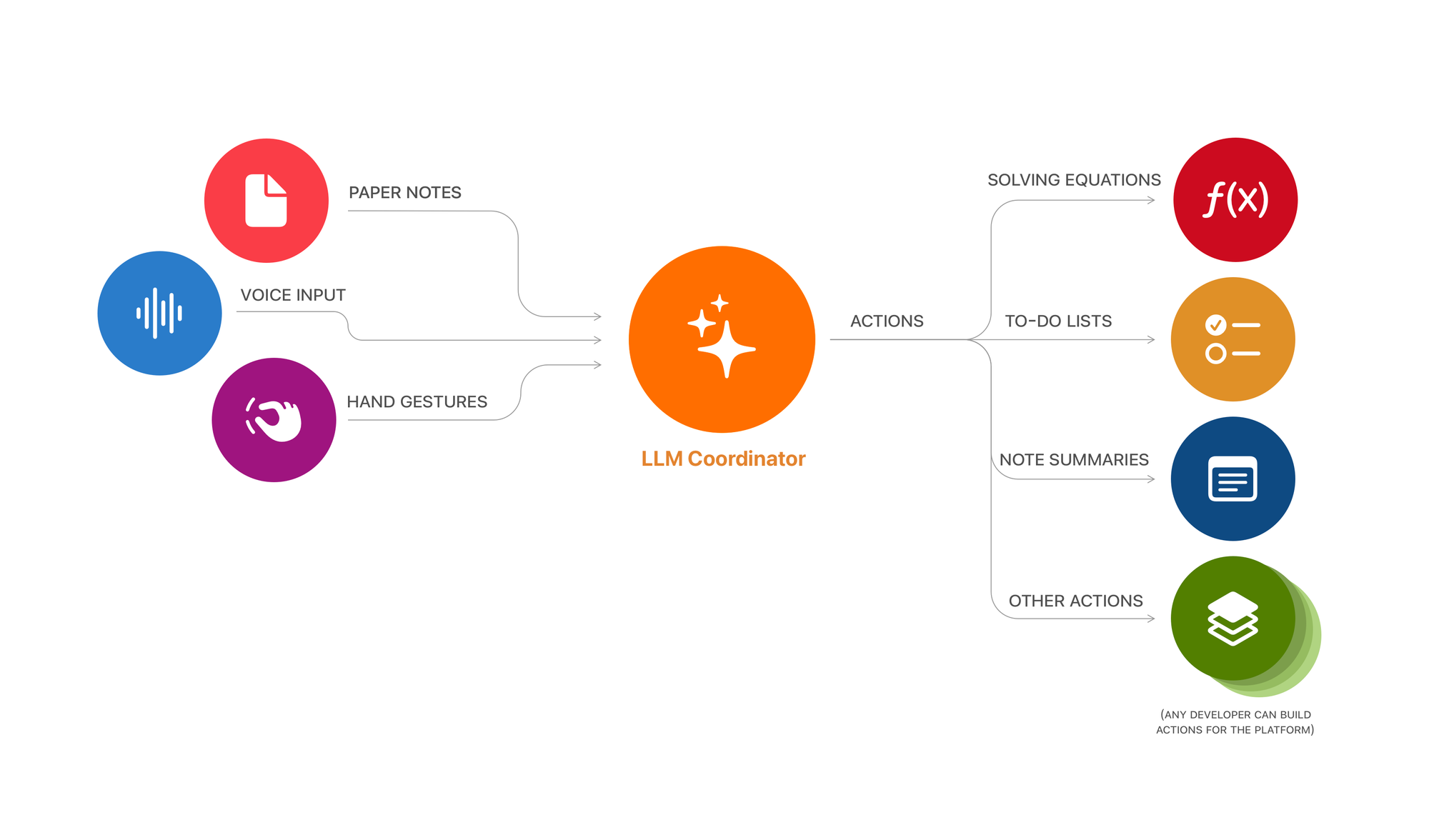

The Thought Lamp isn't just an appliance for Math Problems

The thought lamp expands its actions and turns it into a physical and digital platform that allows anyone to build actions for it. Moving beyond just solving for students focus to a vision of augmented, ambient computing.

The Era of Techno-Centrism is Over

The success of the App Store brought with it the notion that software in your pocket could solve a multitude of problems, leading us into an era where tech took the center stage.

But as problems become more complex, and technology's impact grows, it's become increasingly clear that technology alone is not enough. It's only part of a bigger system that the problems and their solutions live in and when we start looking at those systems, tech's role in the solution space is hardly the center.

Designing emerging technology platforms with a systems lens, also marks a shift, where the understanding of the system, people and the platform becomes central to the solution rather than the technology itself.

Further Reading:

- H. W. J. Rittel, “On the Planning Crisis: Systems Analysis of the ‘First and Second Generations,’” Bedriftskonomen, vol. 8, pp. 390–396, 1972. [Online]. Available: http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/agile/a%20-%20hold/Rittel-Planning_Crisis.pdfdougengelbart+1

- S. L. Star and J. R. Griesemer, “Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39,” Social Studies of Science, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 387–420, 1989. https://www.jstor.org/stable/285080

- D. H. Meadows, Thinking in Systems: A Primer. White River Junction, VT, USA: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2008.

- D. C. Engelbart, “A research center for augmenting human intellect,” presented at the 1968 Fall Joint Computer Conference (commonly known as the “Mother of All Demos”), San Francisco, CA, USA, Dec. 9, 1968. [Online].https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yJDv-zdhzMY

- B. Victor, “Inventing on Principle,” lecture presented at the Canadian University Software Engineering Conference (CUSEC), Montreal, QC, Canada, Jan. 2012. [Online]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EGqwXt90ZqAcsis.pace+1

- D. C. Engelbart, Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework. Menlo Park, CA, USA: Stanford Research Institute, Oct. 1962. [Online]. Available: https://www.dougengelbart.org/pubs/papers/scanned/Doug_Engelbart-AugmentingHumanIntellect.pdfarchive+1

- A. Dunne and F. Raby, Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2013.