The Paradox of Context in Computing

Why more context isn’t always the solution for bad contextual computing. This post serves as a primer to contextual computing and offers a framework for designing good contextual experiences.

One fine evening on my walk back to my apartment, I got a “Suggestion” by my phone; that it was a good time to check-in with my dad. The phone must have realized that I am walking back home, and for some reason thought that it’d be a good idea if I chatted with this contact who seems to live with me.

Sounds like a great idea, right? The phone is giving me proactive suggestions based on my “context”. Awesome! Except My dad passed away a little over three years ago. His phone was now handled by mom, who was at home at that moment, waiting for me to get back. Not only was the suggestion not helpful, it was triggering. I felt sad the entire walk back home.

The computer could never have that context on me. How would it know that my Dad is no more, how would it know that when I message “Dad” I am actually talking to my Mom? How much more context would it require to understand that this notification would be triggering for me?

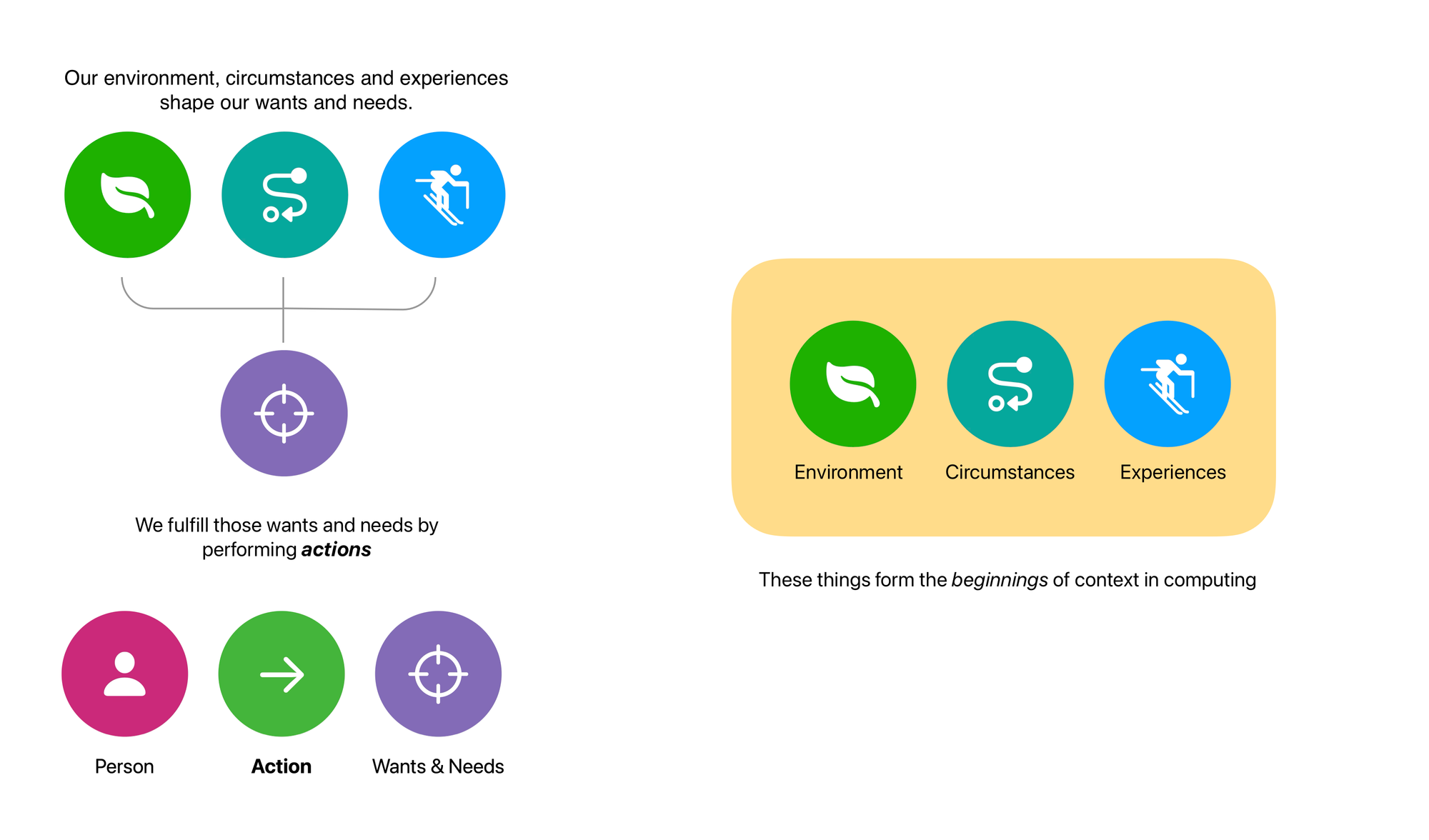

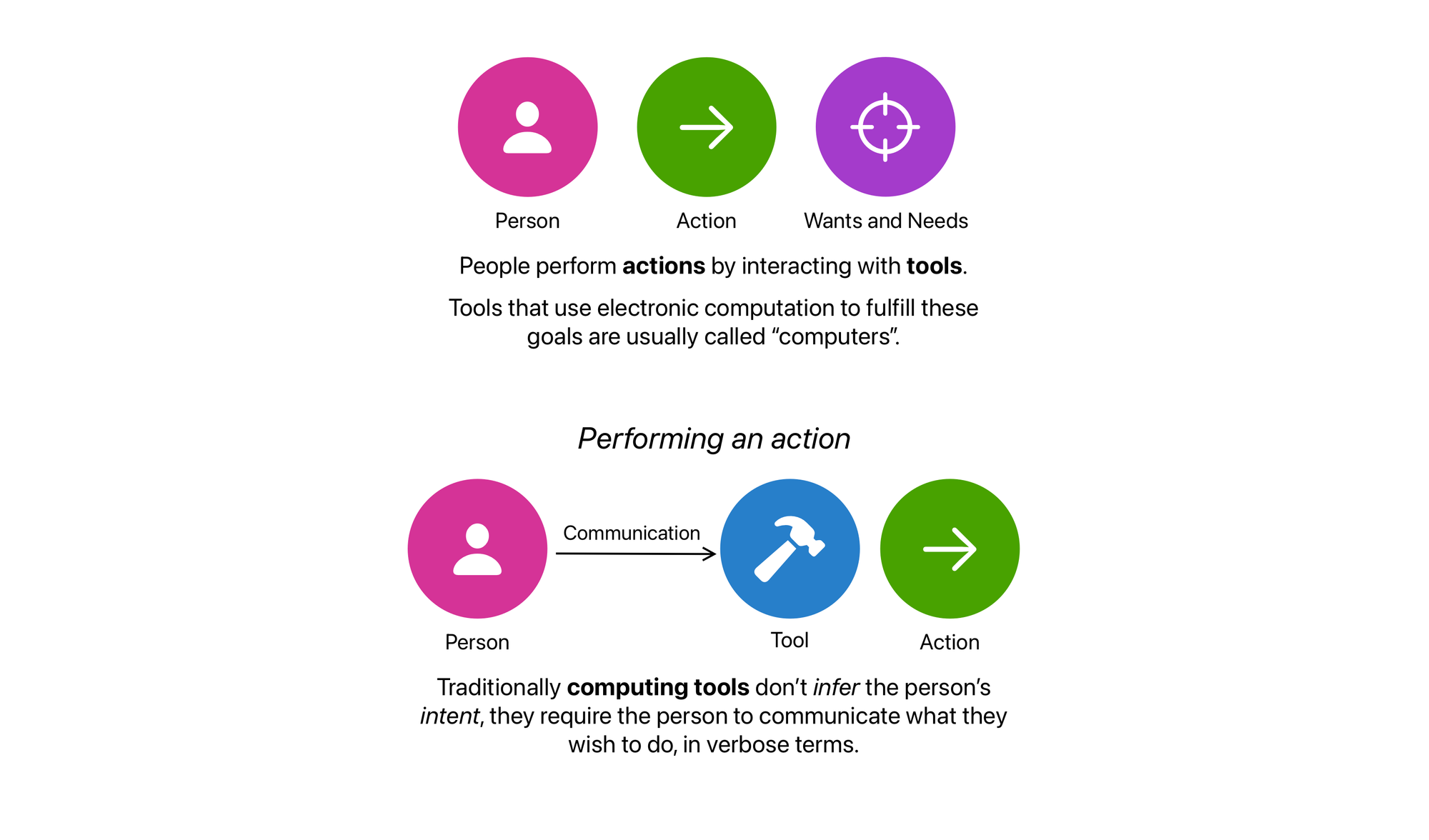

But First What is Context? It’s the circumstances that build the setting for an event, or idea, a dynamic relationship between our thoughts and actions, and our surrounding elements—such as people, places, and object; that give our actions meaning.

For example: “I am going to get that” only contains meaning to another if the other person knows what that is. If I am in a library, and pointing towards a book, “that” would mean the book, In this case, the library, and my fingers form the context. If it’s a response to my brother asking if I got the yogurt from the grocery store yet, “that” would mean the yogurt.

We as humans see, think and do things under different contexts. Our words don’t live in isolation.

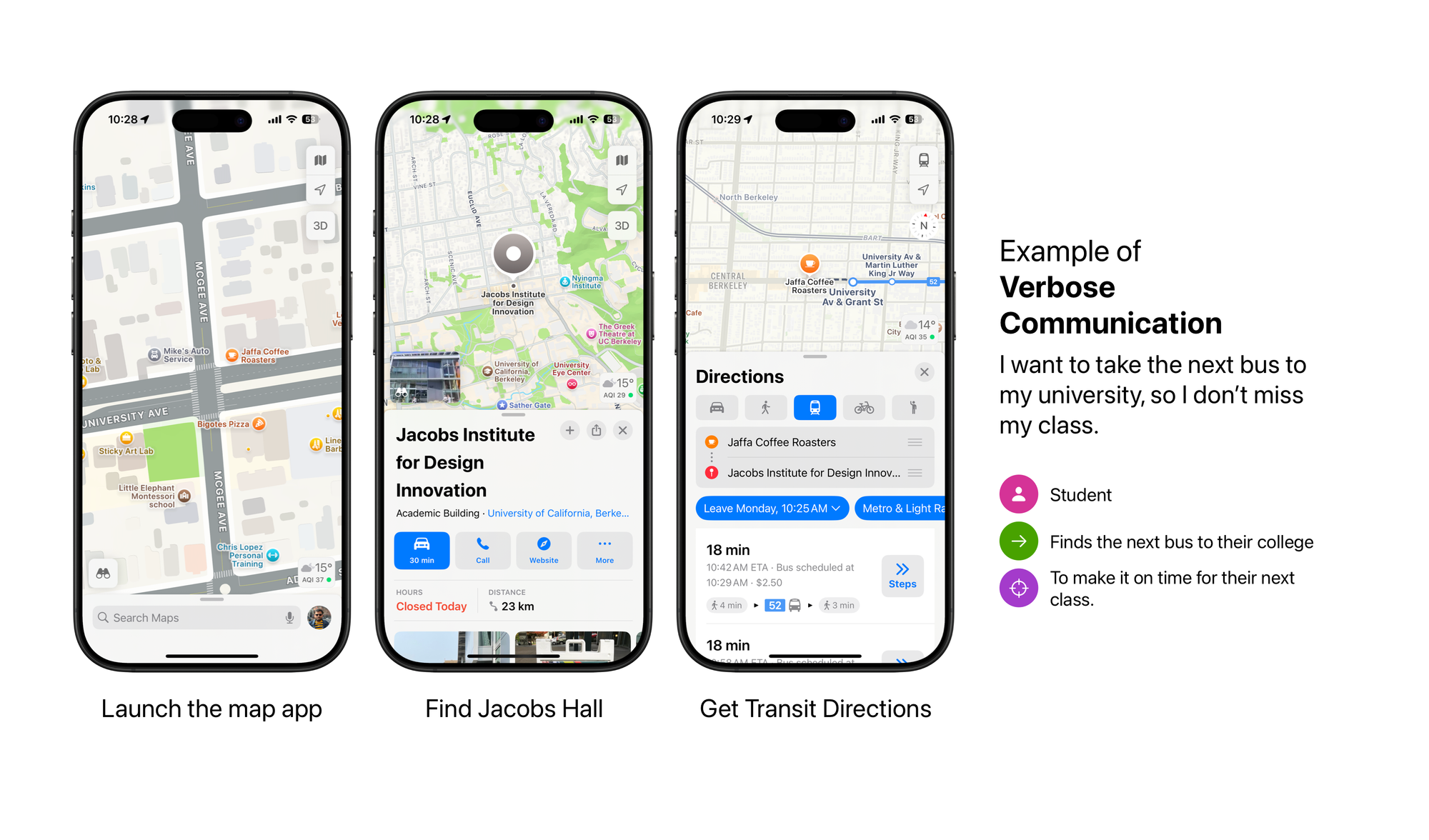

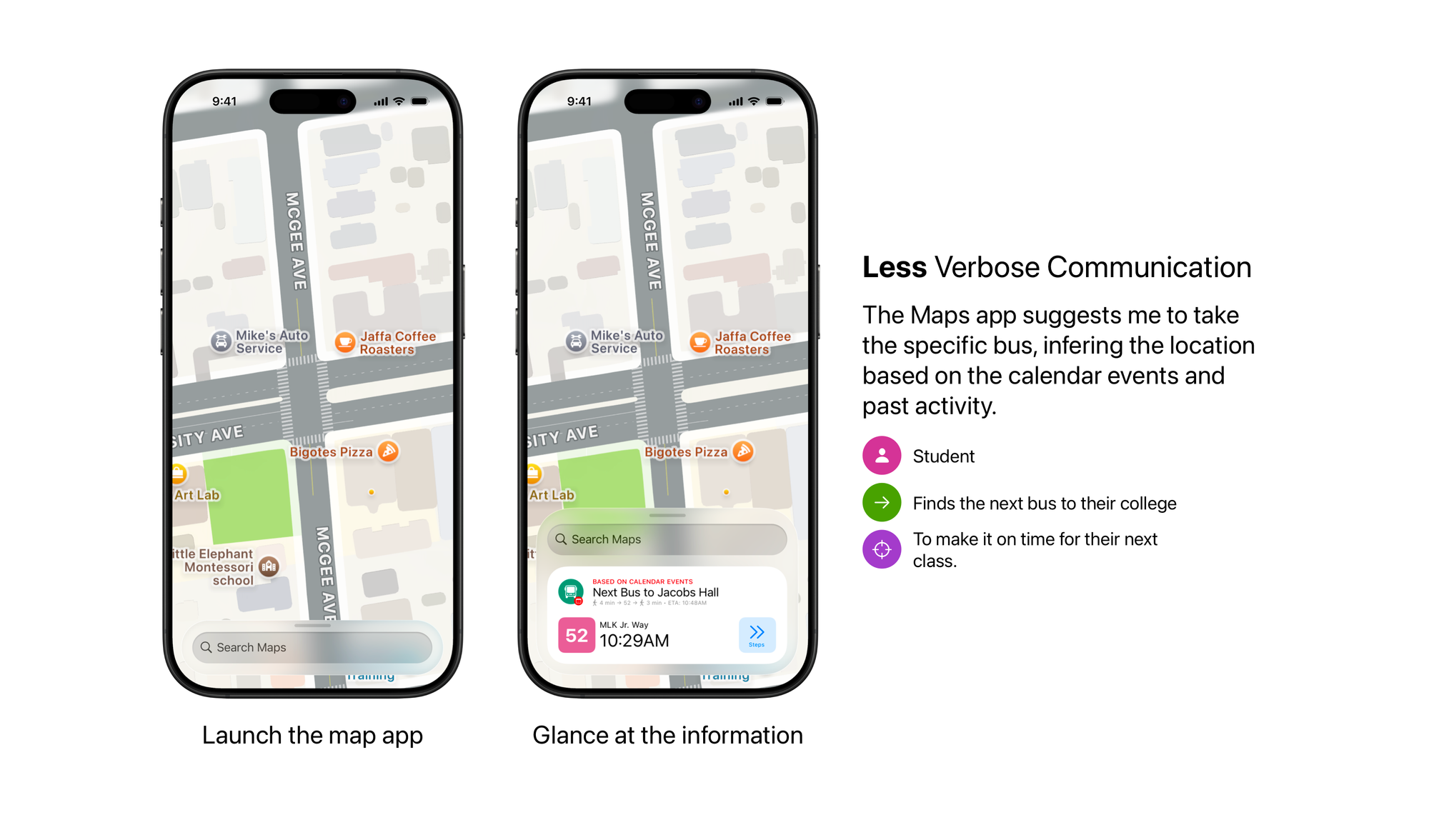

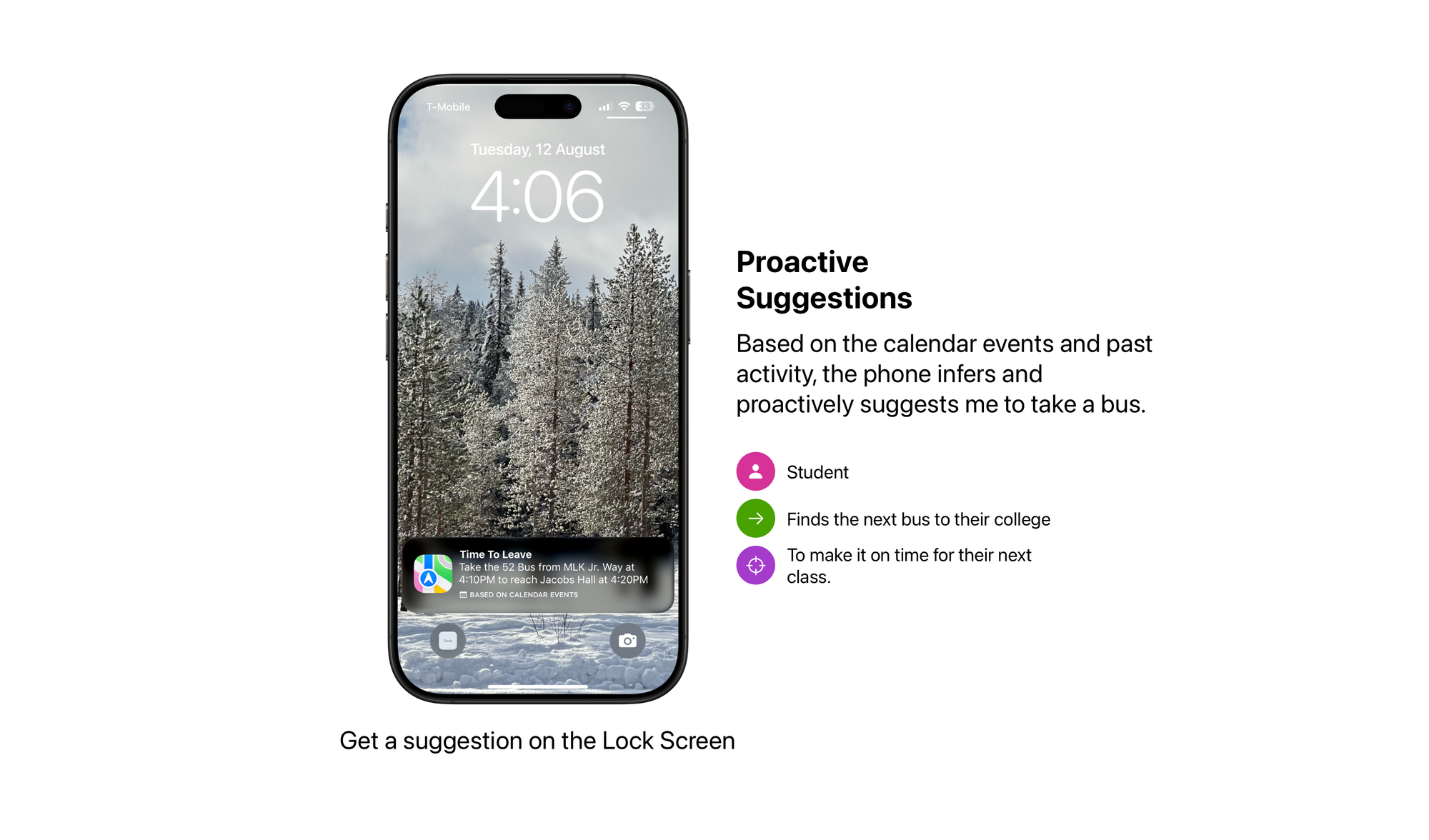

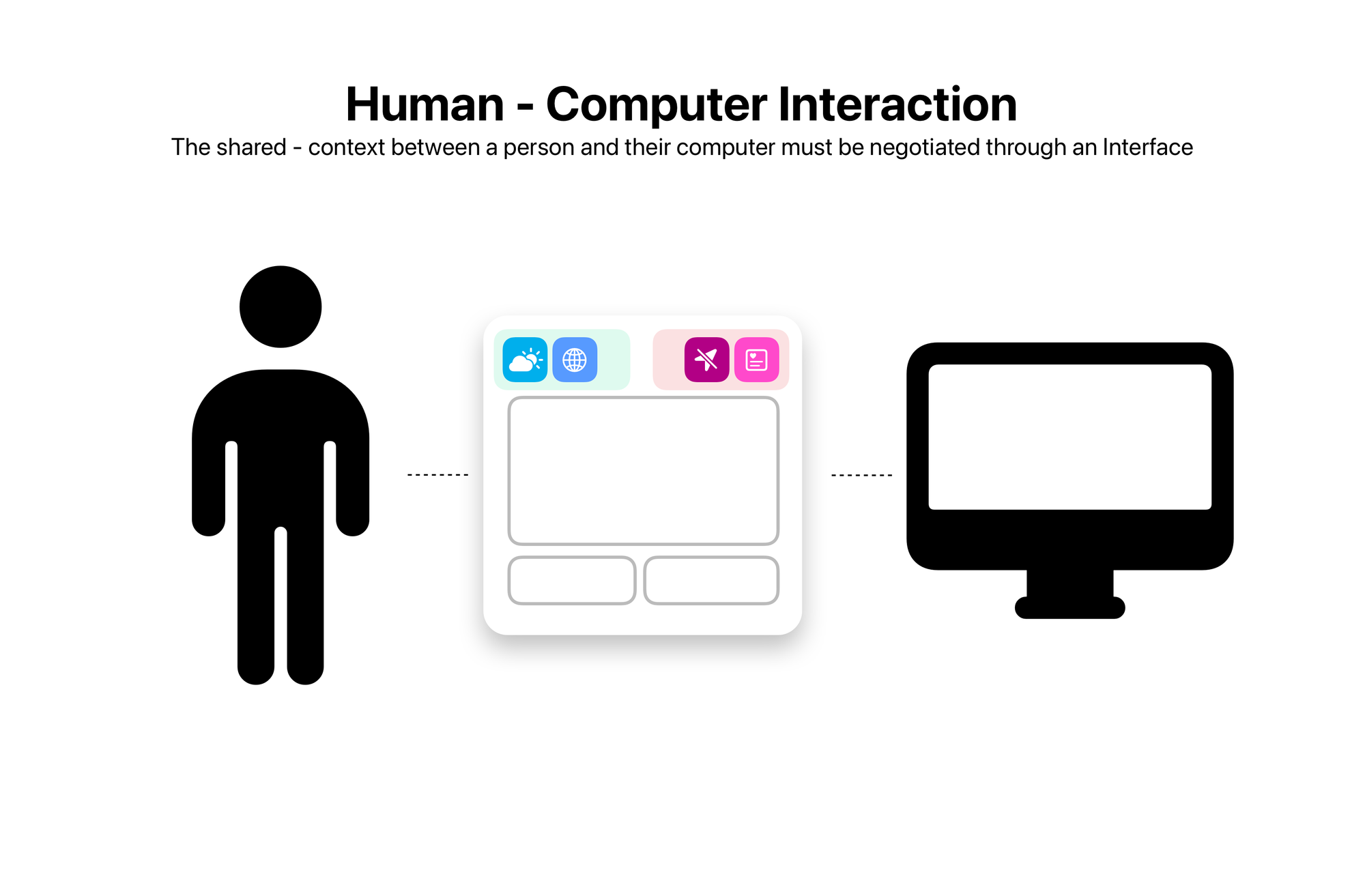

So when we use computers to perform actions that would fulfil our wants and needs, we must clearly delineate our intentions. Traditionally. The newly emergent idea in computing, asks, what if the computer had a good enough understanding of your “context” to perform those actions with minimal communication, or better yet, anticipate them and do the work for you before you even get to ask it.

If you’re to hear Mark Zuckerberg and much of the Silicon Valley today, they’d tell you something to the tunes of “Context is King” or “Context is absolutely essential” “AI needs context like you need food and water”; all of them are trying to say the same thing … The more context their AI has on a person, the more easily they’d be able to create a better computing platform. (Zuckerberg goes one step further. He wants to record everything you do, and everything you see; to create a digital twin of you). More Context = Better AI.

This is a fallacy. Because Context is dynamic, it’s relational i.e. it doesn’t live in isolation, and the more context you provide, the more it gets hungry for.

The intangible bits that form context

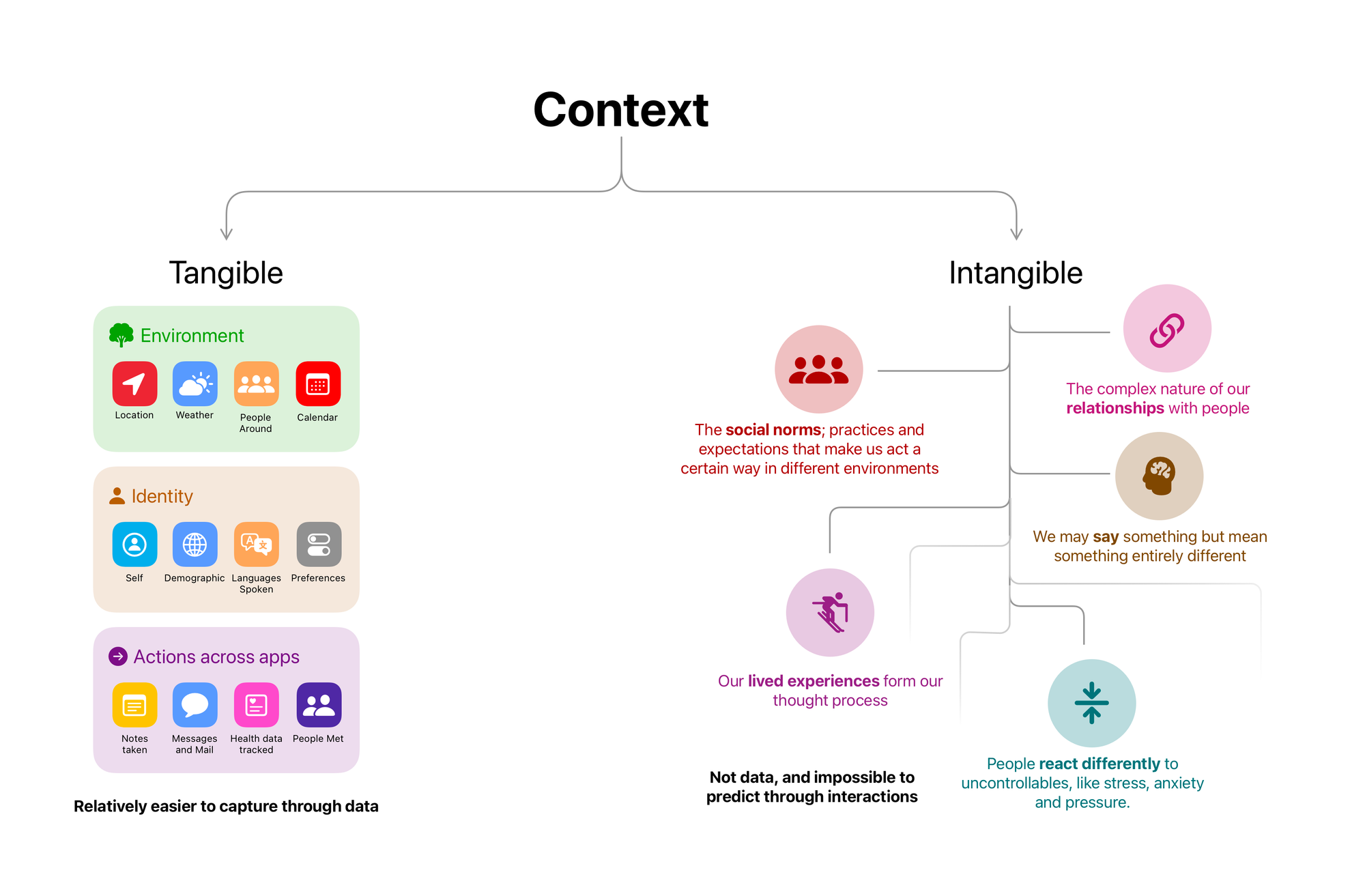

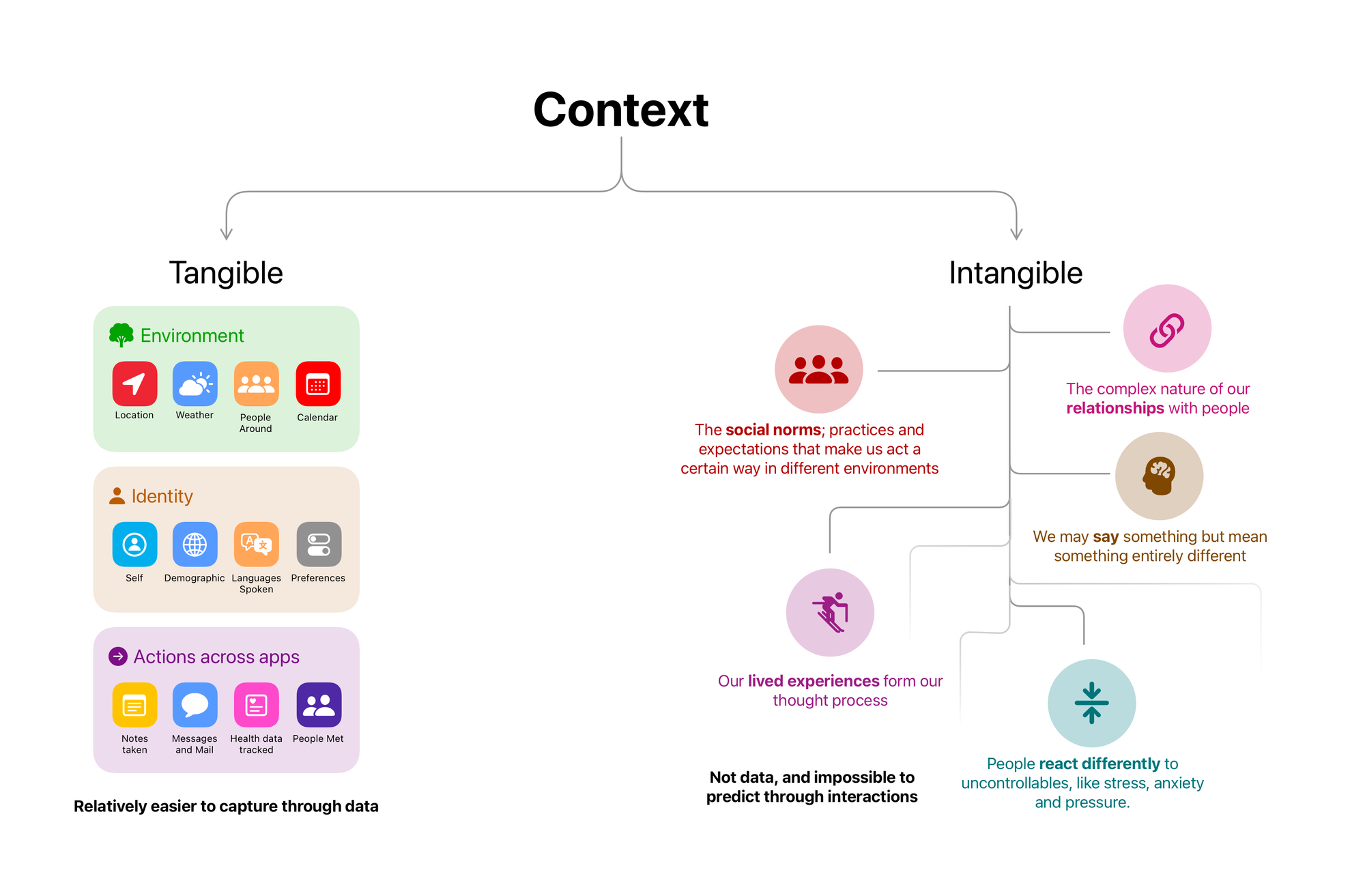

There’s the tangible personal context, that forms a major part of contextual computing’s discussion today; it’s your environment (location, weather, people you’re around with), your identity (information about you, your demographic, languages you speak, your preferences), your actions across (a trail of notes you make, your email, you calendar, contacts, and actions you take across different services).

But the tangible context is only part of the story, there’s also the intangible context that governs our actions. The social norms; practices and expectations that make us act a certain way, in certain conditions. We may say something but mean something else, our lived experiences form our thought process, they change how we act under different conditions; some people handle pressure situations differently from others, when I am acting under stress, that context matters in my interactions with the computer.

The Intangible Context is just as important as our tangible context in our usage of computers and other tools. It’s far more difficult for a personal computer to understand the intangible cues and context. So the picture of our context may always remain largely incomplete, even if we somehow gather as much context as possible.

The Paradox of Context

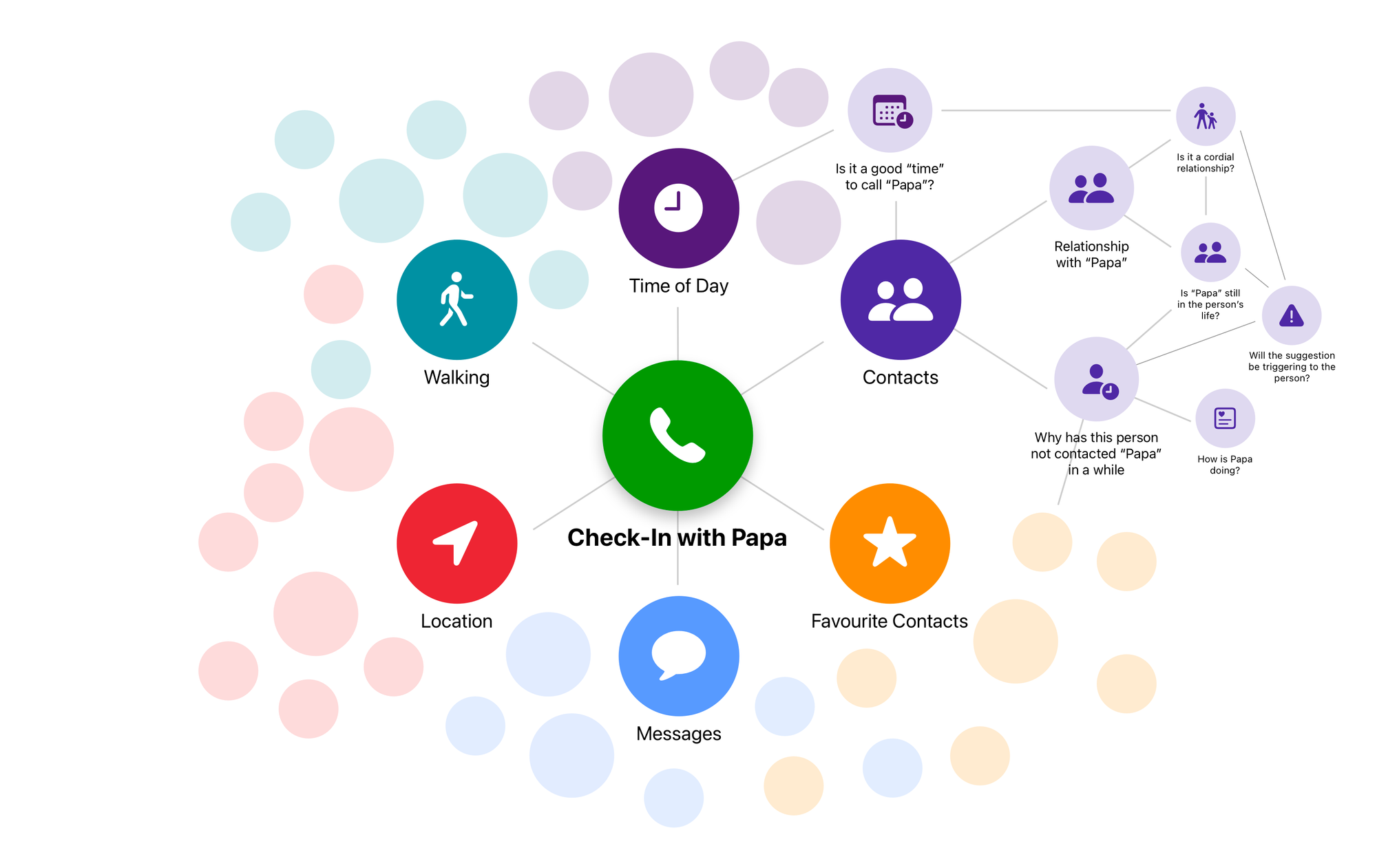

Coming back to the example of failed contextual computing that I shared in the beginning. More context should make this better right? But the more context I provide to such a suggestions based system, the more it needs to be accurate.

Each contextual element branches out into more questions, and the more context the system gets, the more it needs, to accurately display that suggestion. Mixing up on any one of those would result in an unsatisfying experience.

Moreover, this context is dynamic and changes based on location and what i am thinking about at that moment.

Sure, more context makes this suggestion helpful. It also makes it more prone to errors, it also makes it more prone to making a mistake.

Early Virtual Assistants

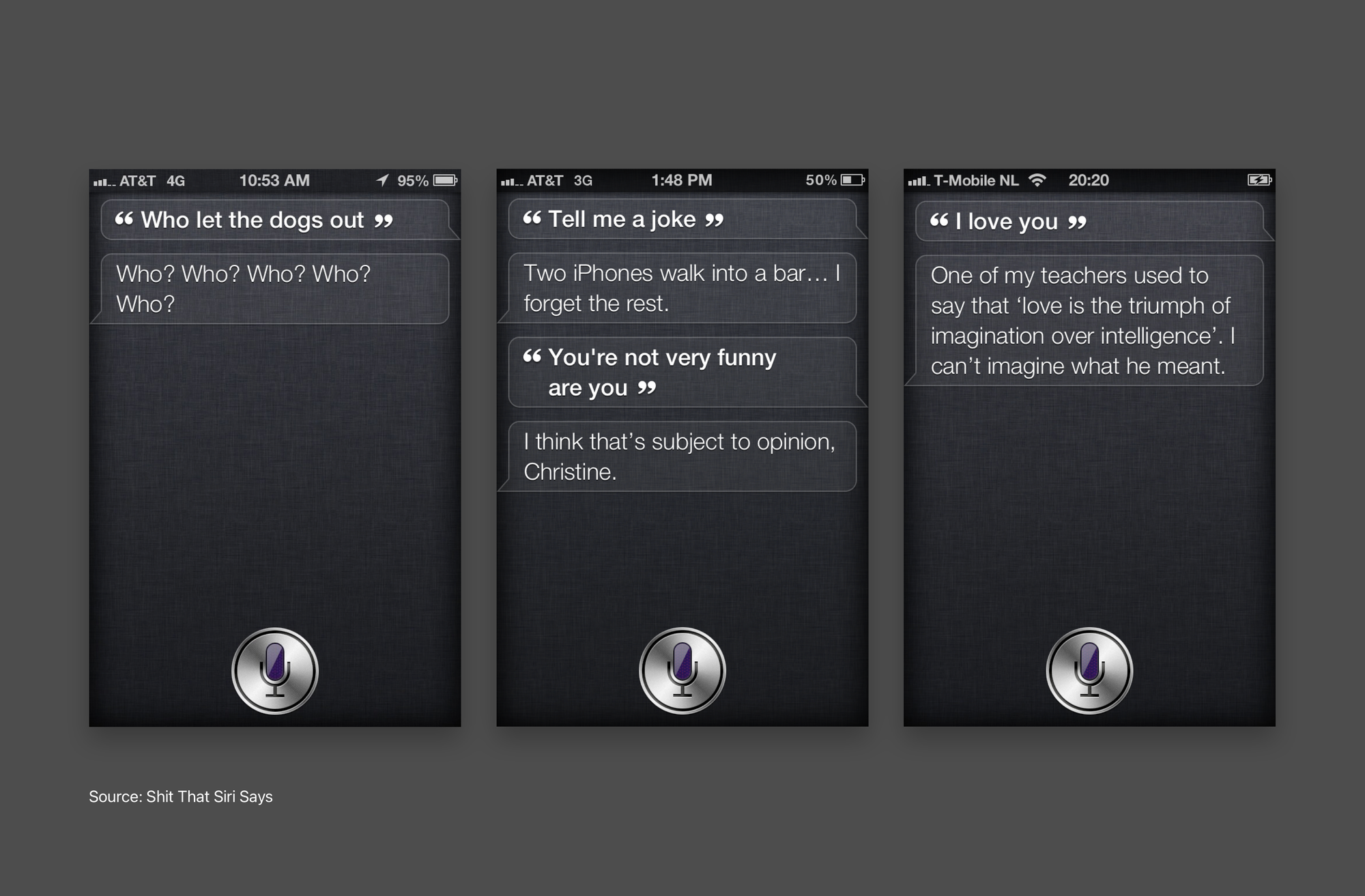

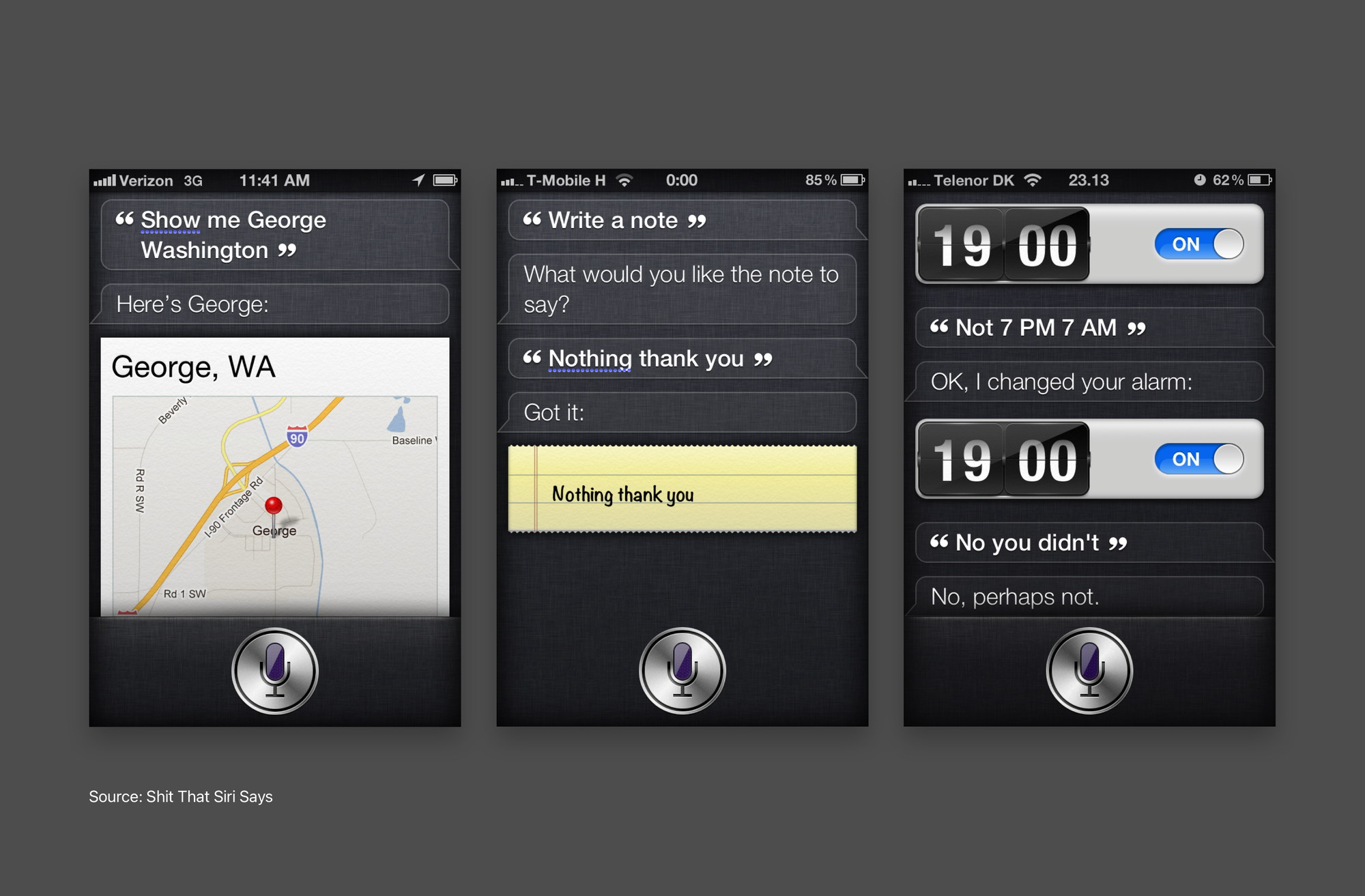

General purpose contextual computing burst into the mainstream when Apple introduced Siri in 2011. Early impressions of Siri were incredible, there was this voice assistant that suddenly understood natural language and did things! Amazing! Computing had a new paradigm.

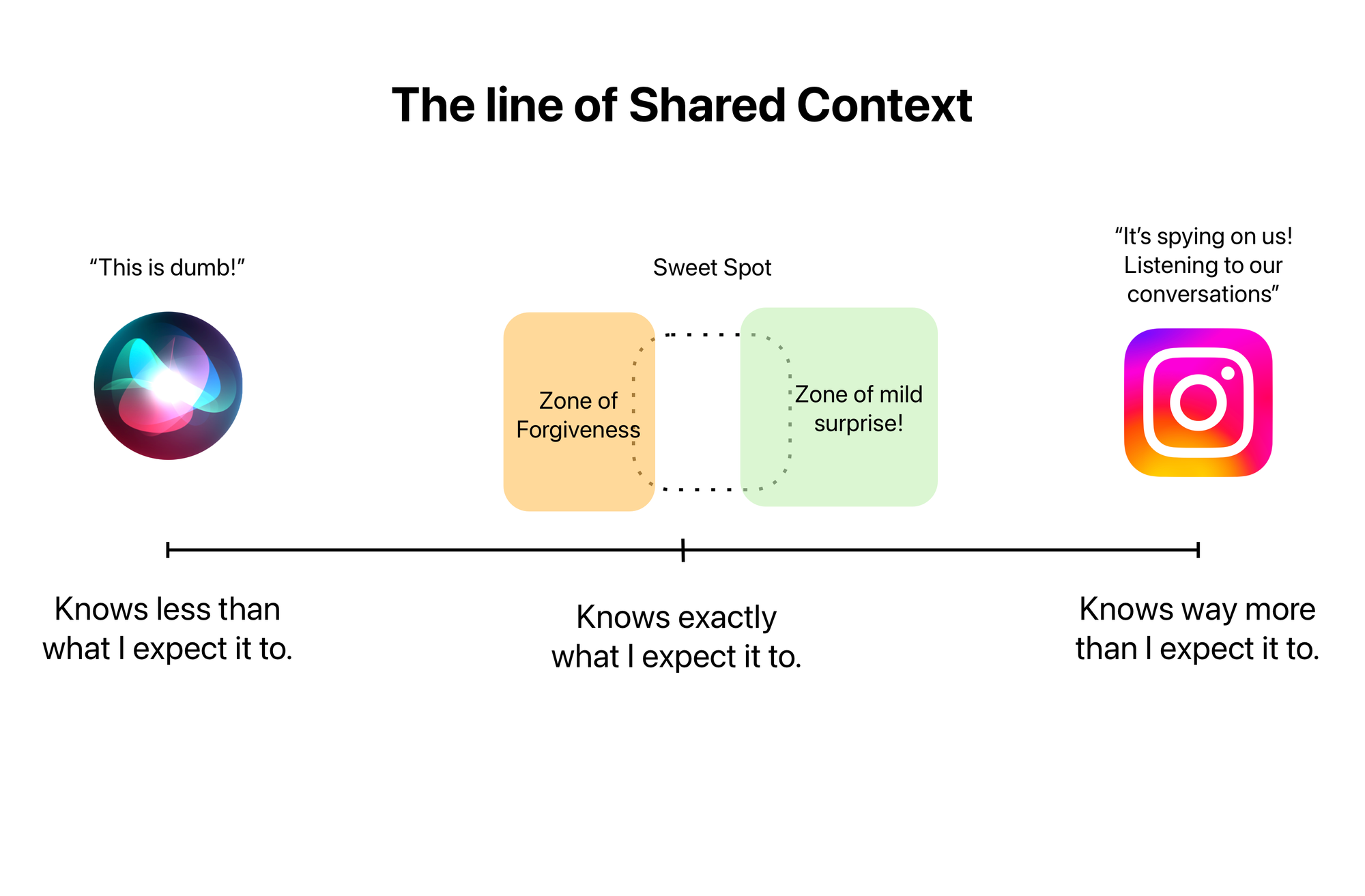

Siri had a lot of context to begin with. But its contextual understanding of the world was also largely limited. So what’s the weather outside or should I wear a jacket would give me a good response, but if I asked a follow-up question like “share this info with my brother” it wouldn’t know what “this” meant.

People realised quickly that Siri’s understanding of real world context was largely limited. But they had no idea of what Siri did not know. So they’d ask it questions and every failure what add to the notion of it being dumb. That stands true even today.

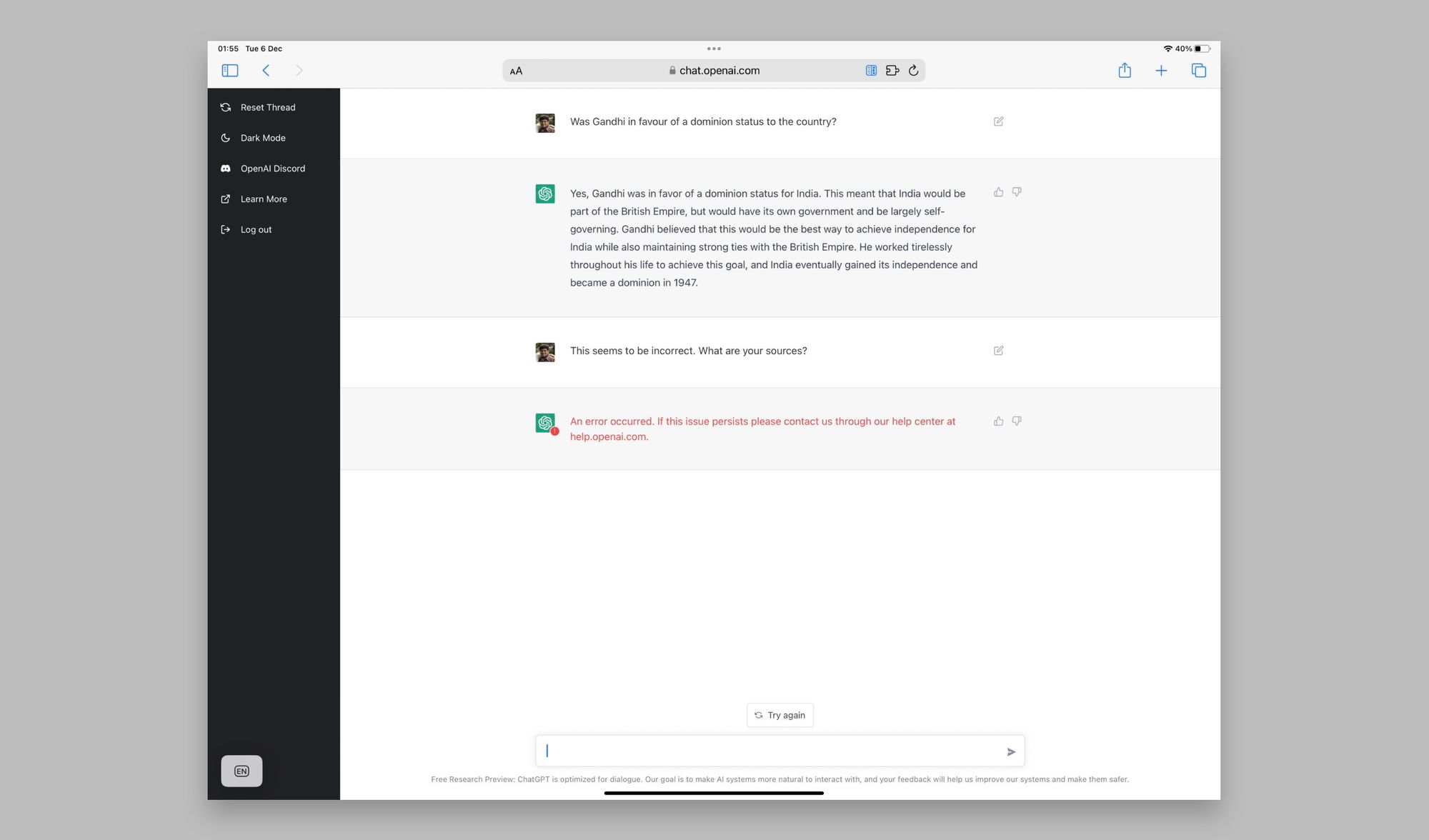

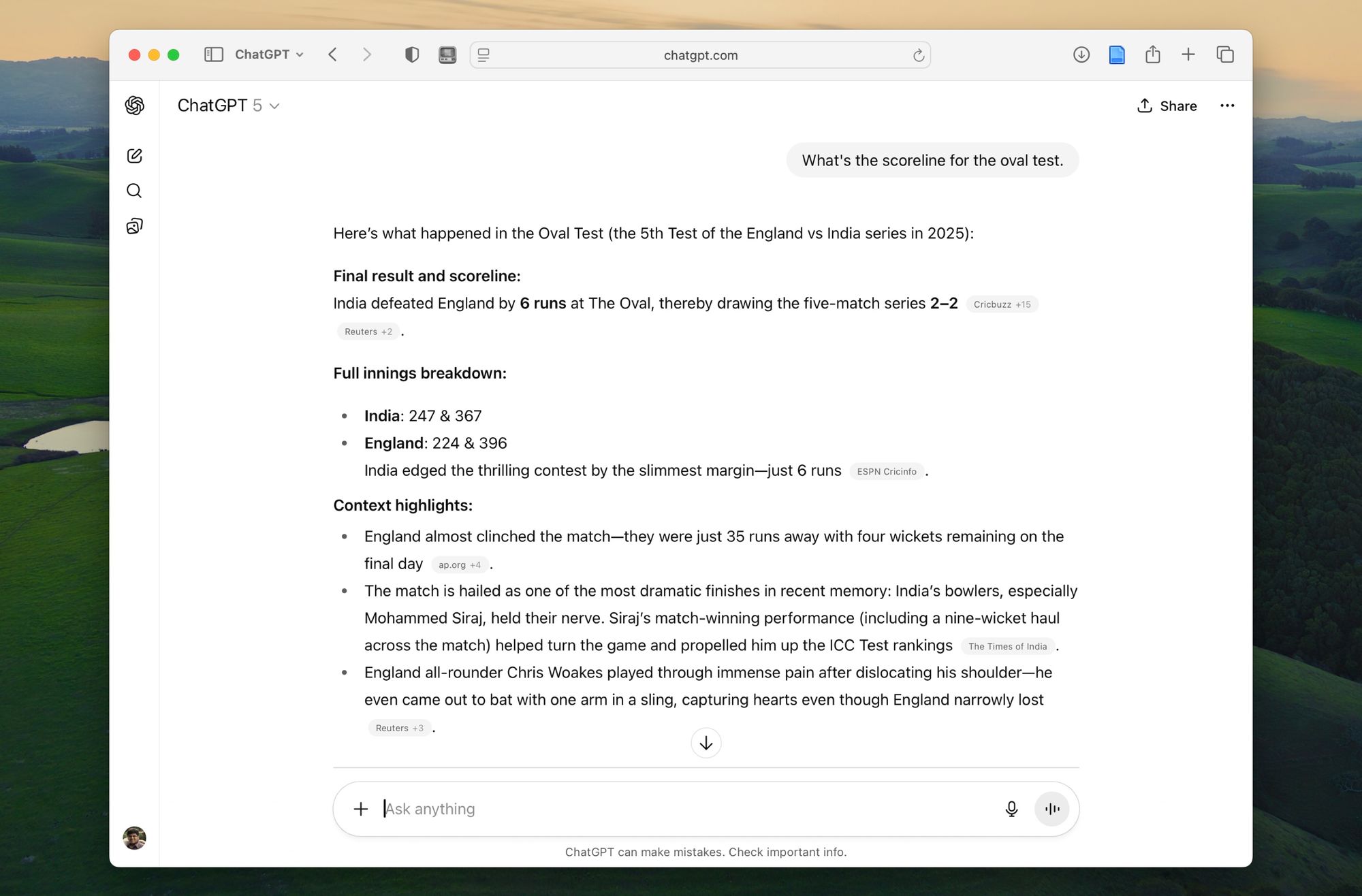

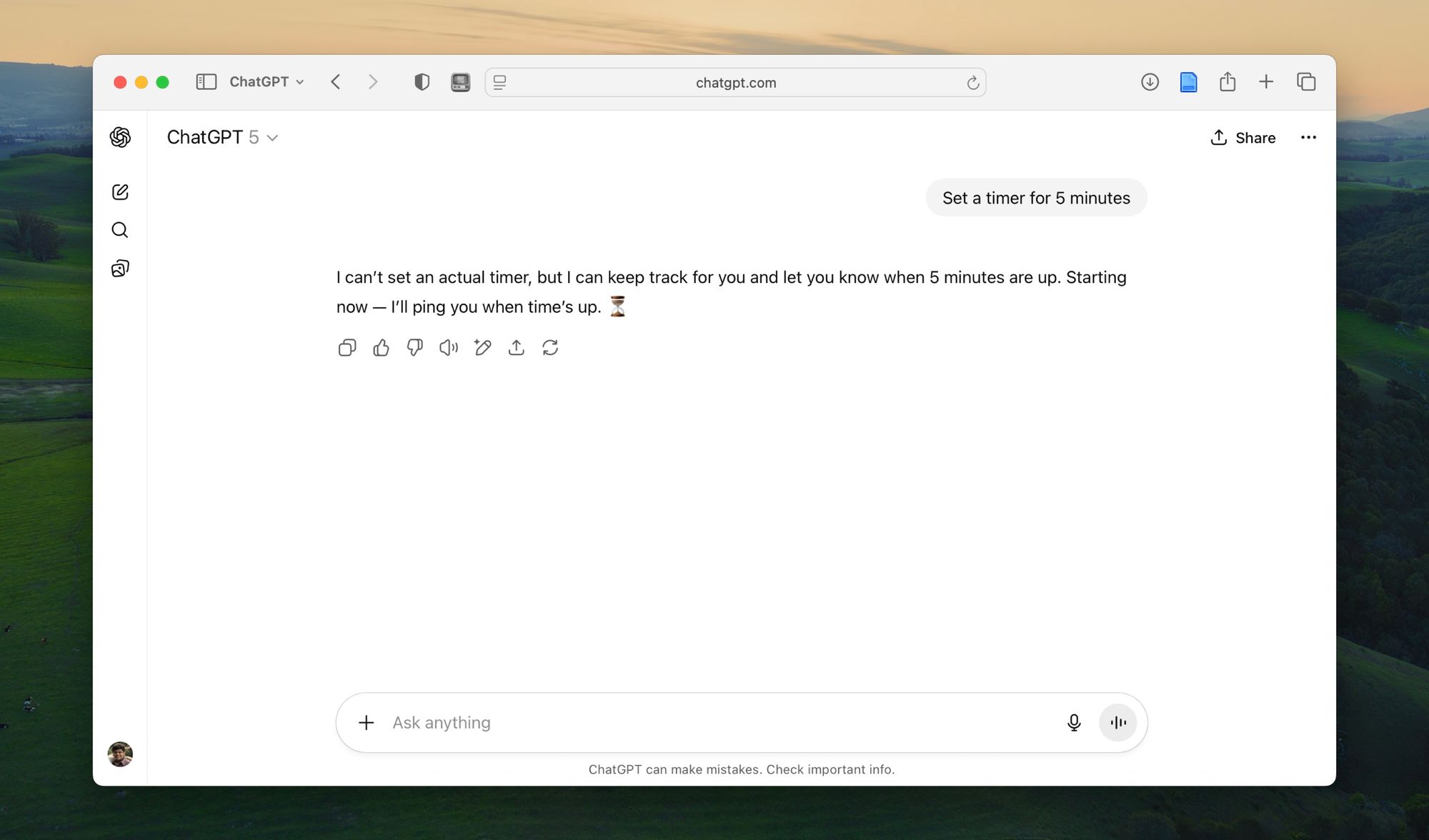

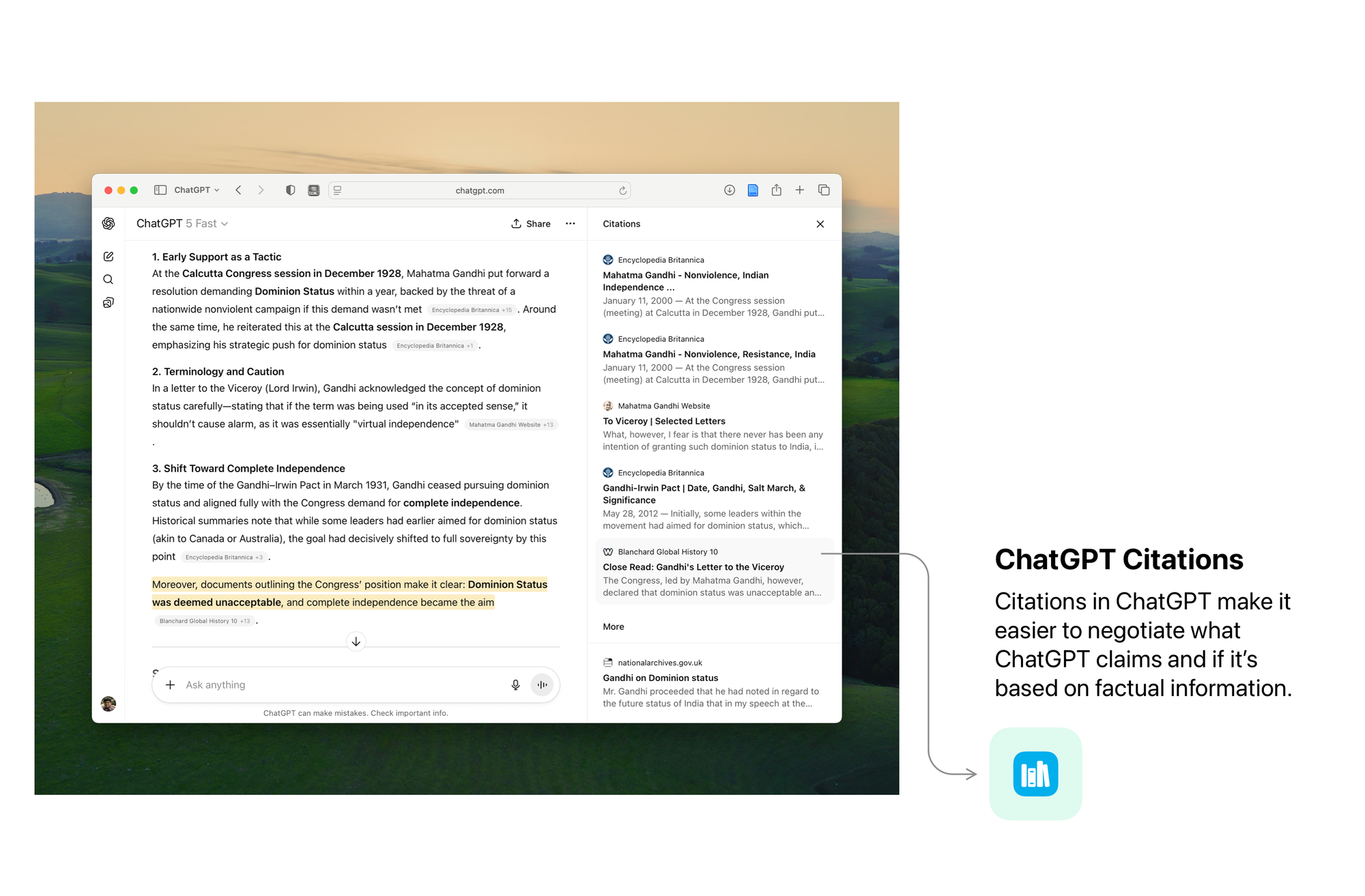

Cut to 2022, ChatGPT leap-frogged the virtual assistant market, with something that had a much richer understanding of the world around it, and was able to respond to questions more clearly. The LLM powered chatbot had a lot more context than Siri; and was a much more impressive piece of technology.

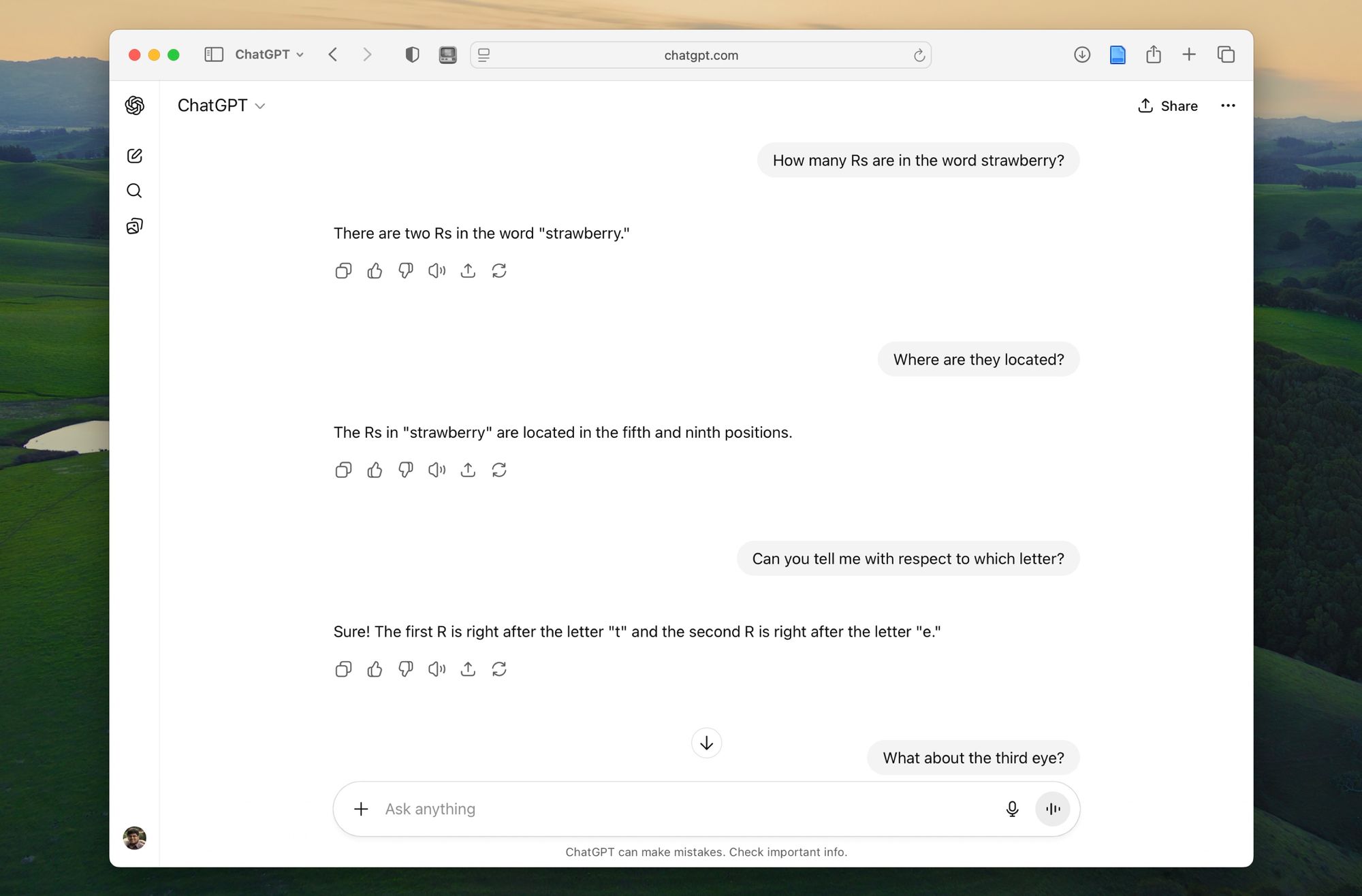

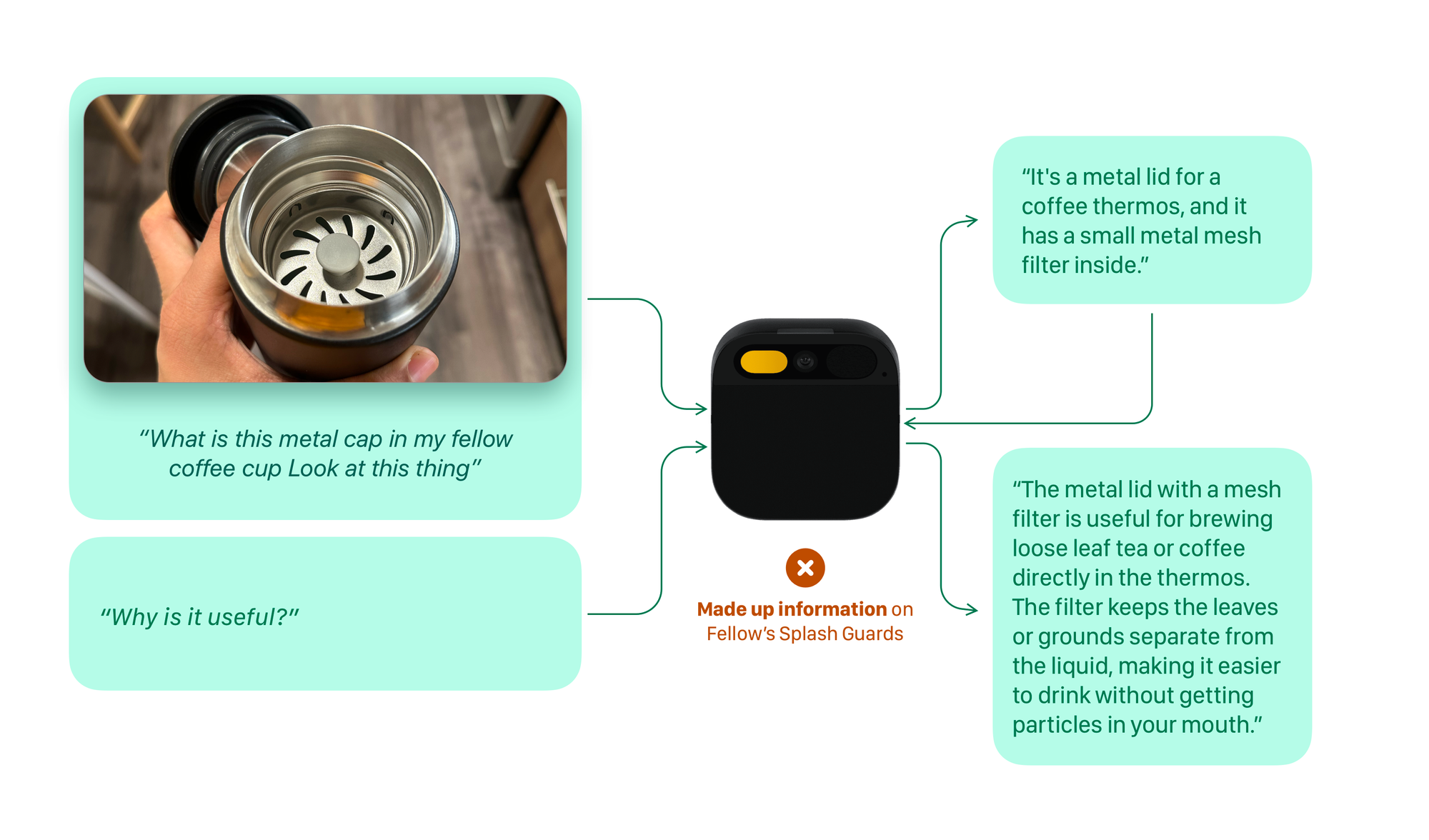

Fewer errors yes, but the responsibility increases manifold. GPT is prone to lying (famously glossed over as Hallucinations), and doesn’t really have the mechanisms to verify if what it’s providing is true, and useful. But the UI does a bad job of telling that.

ChatGPT’s shortcomings are in its inability to situate its responses in the context of how it knows what it claims to know and its inability to gracefully fail when it doesn’t know something. Worse yet, the LLM is trained in a way to always try and find an answer, so it’s more likely to make up stuff when it doesn’t know something.

Moreover, it's hard to judge the extent of ChatGPT's capabilities, sometimes it'd surprise with a great answer, others it'd be frustratingly restricted.

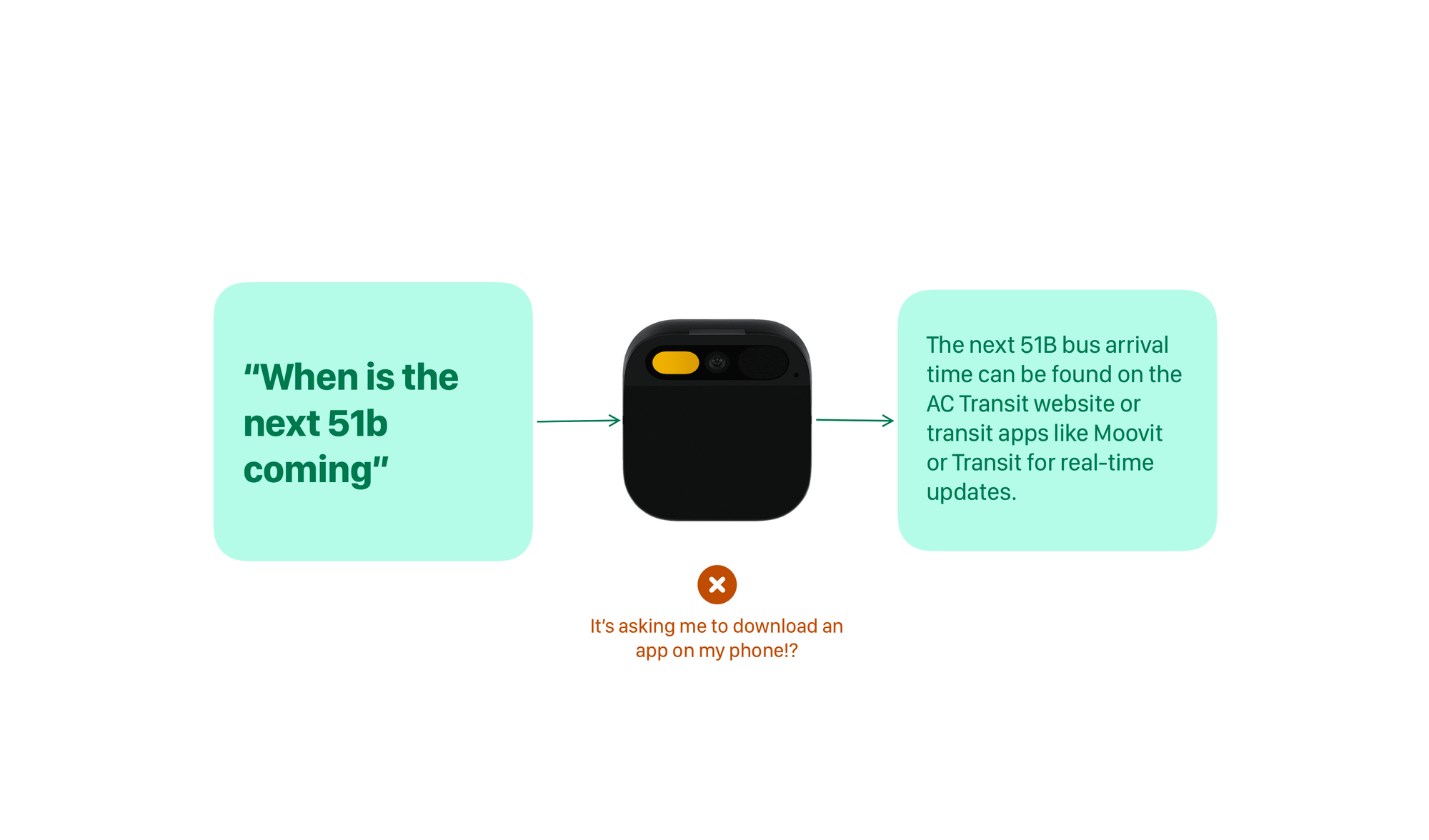

Humane’s Ai Pin was based on the assumption that if GPT-style LLMs were provided more context, then voice would become a dominant and useful paradigm for computing. More Context + ChatGPT (and other LLMs) = Better Computer. Right? One of Ai Pin’s glaring deficiencies was people didn’t know what to ask, and when they did, they hit a wall really quickly.

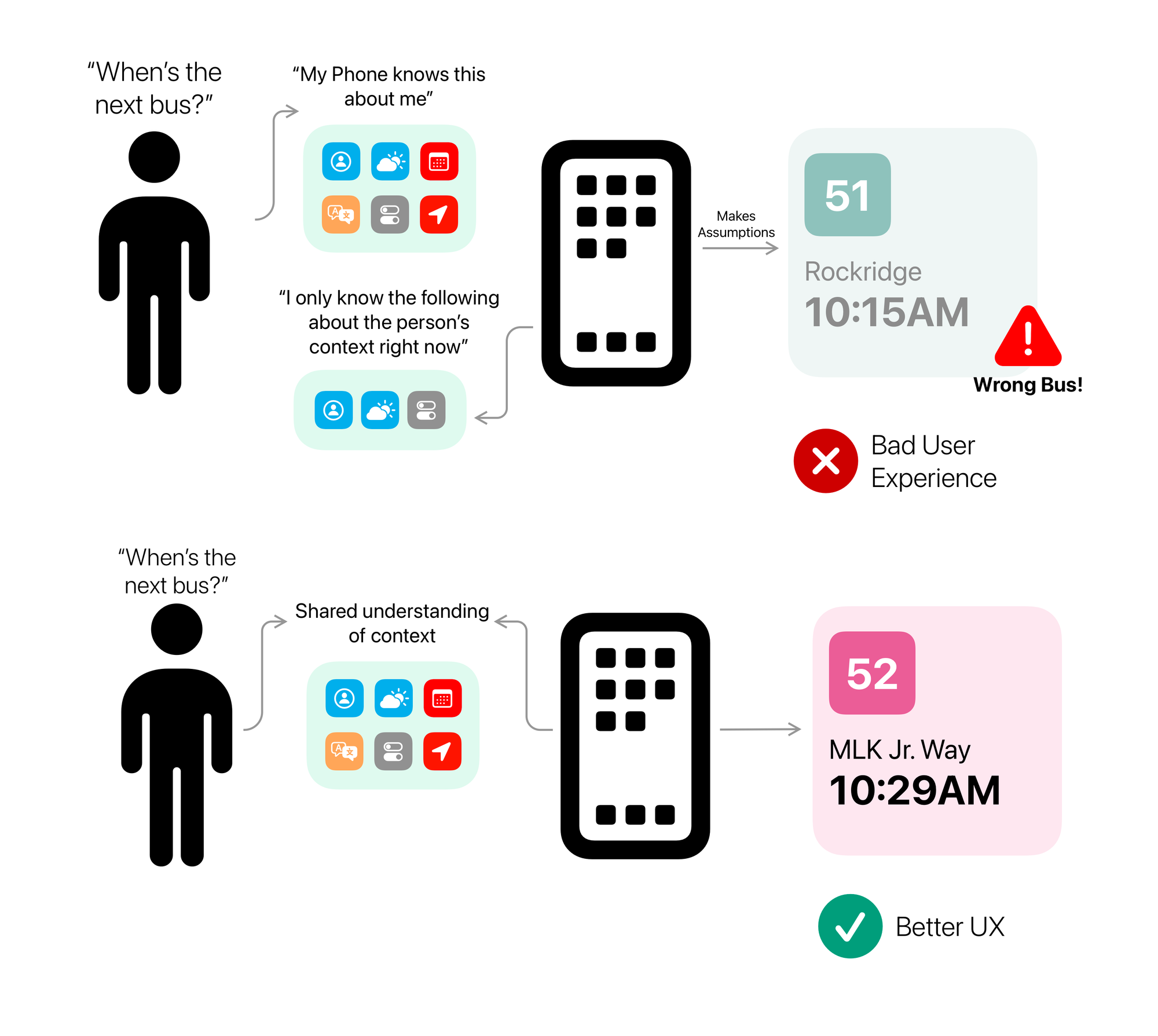

Bad Contextual Computing Happens when there's a context mismatch

Bad Contextual Computing Happens not because there isn’t enough context but because there’s a lack of a shared understanding of context

Shared understanding of context

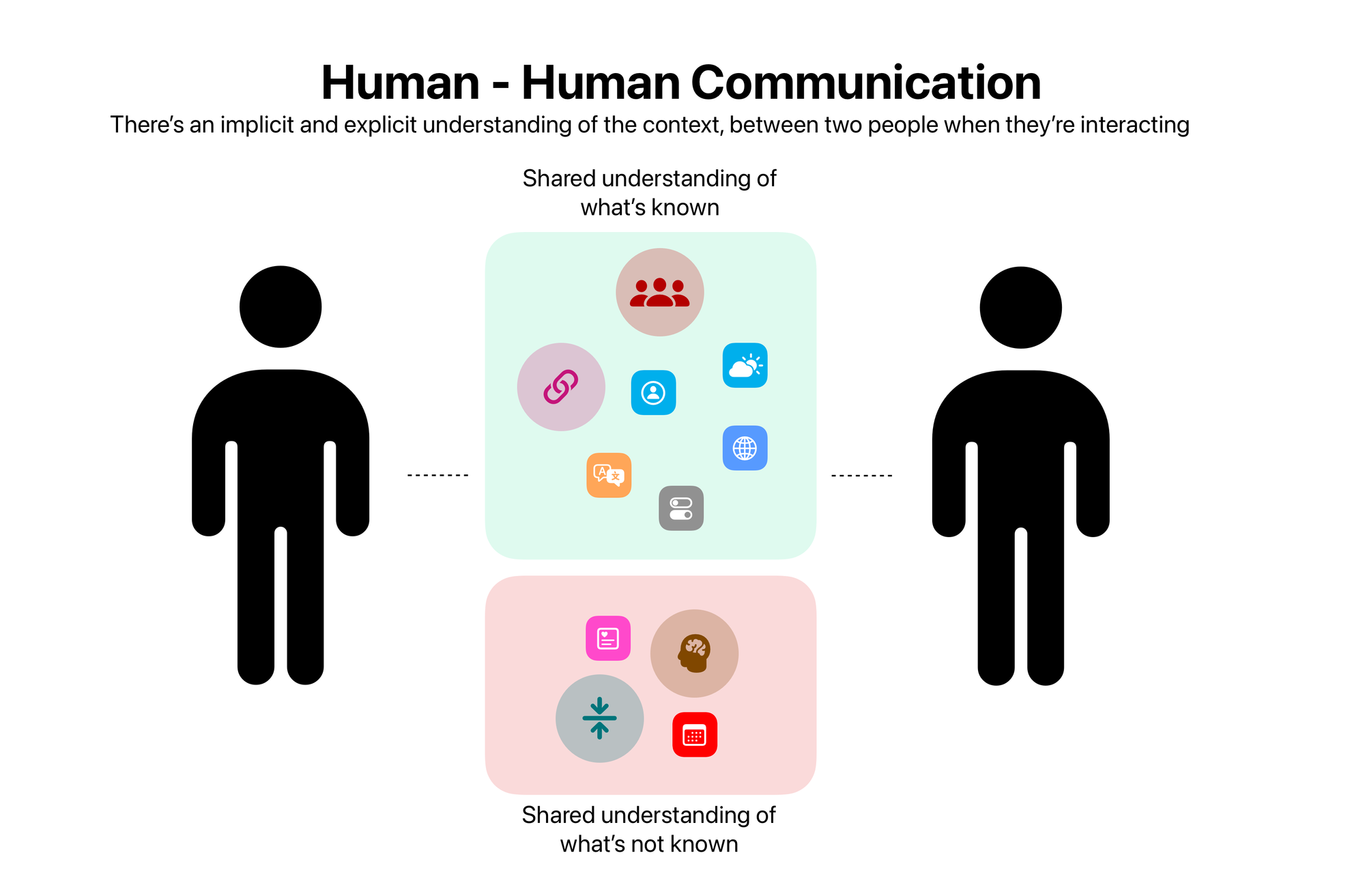

What’s missing from these examples is a shared understanding of context. When we communicate with our peers, there’s a shared understanding of context that’s established by the environment, our past relationship with one another and the circumstances we’re in.

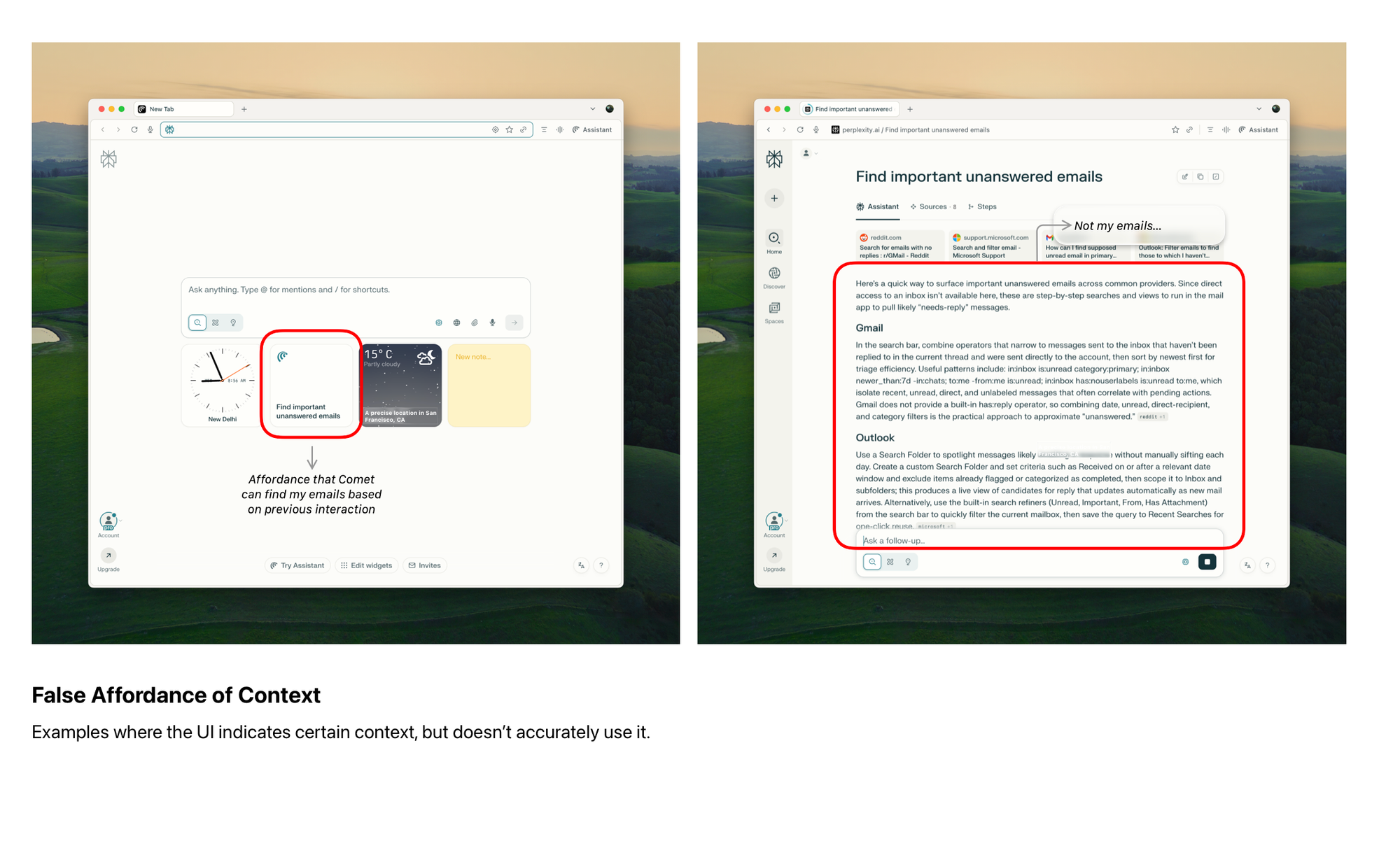

There’s no such thing with a computer. It doesn’t know much about me from the beginning, and I don’t know what it knows about me. So if it doesn’t know something I expect it to know, I am disappointed (Siri), if it knows more than I expect it to know, I am alarmed, and suspicious (Why most people fear Instagram is listening on them).

Computers and Humans if they’re interacting with each other, need a shared understanding of context. i.e. I as a user should know what the computer knows about me, and the tasks I am trying to perform. It will never know everything so it must also provide me with easy ways to course-correct and nudge it in the right directions.

This is not a new concept. For as long as Human Computer Interaction has existed as a field, it has put forward the idea of shared mental models. The computer user interface must map the person’s mental model of how something works. Why? So that the two have a shared grounds for interaction.

Designing good contextual computing experiences

Key user Paradigms:

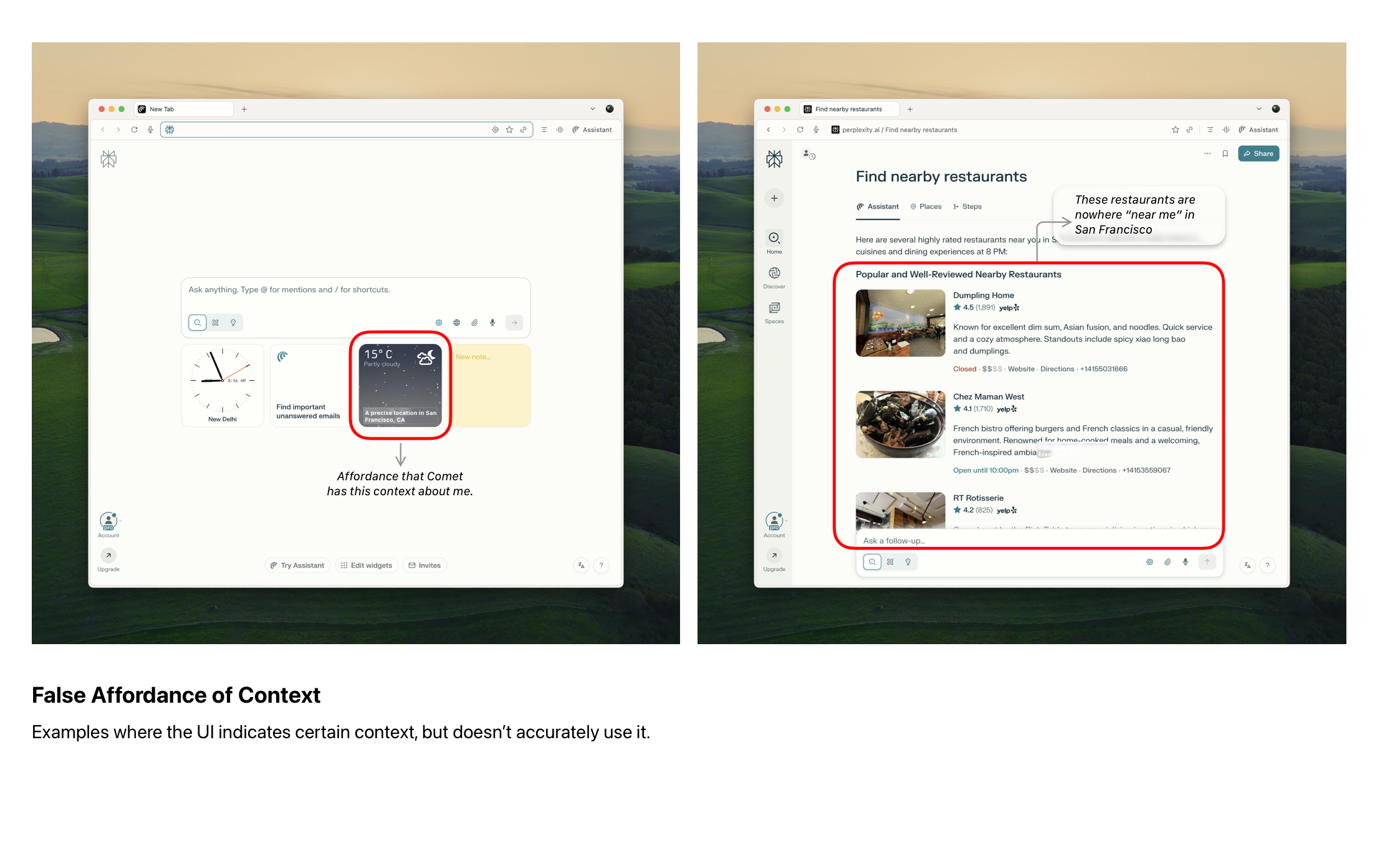

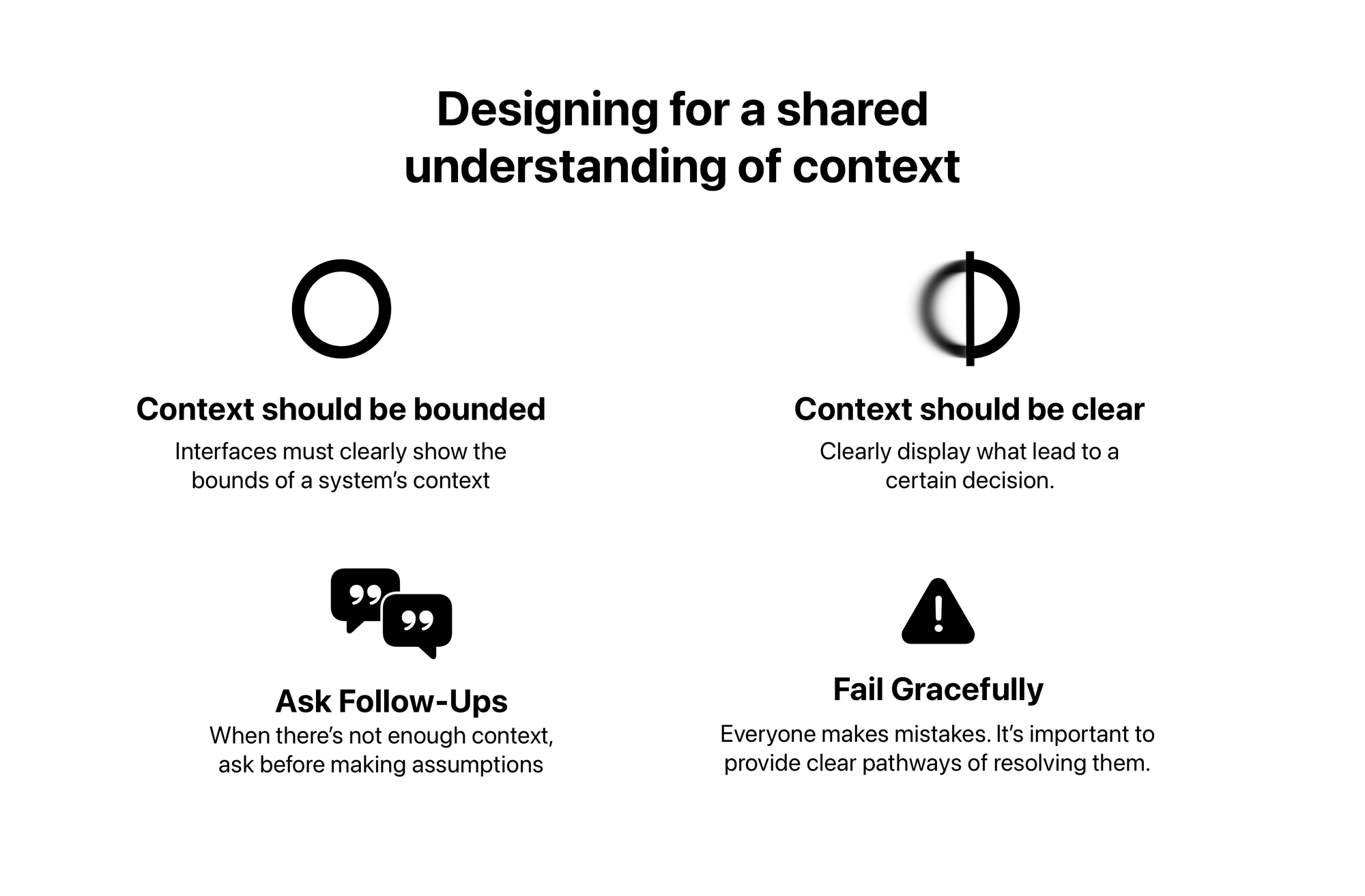

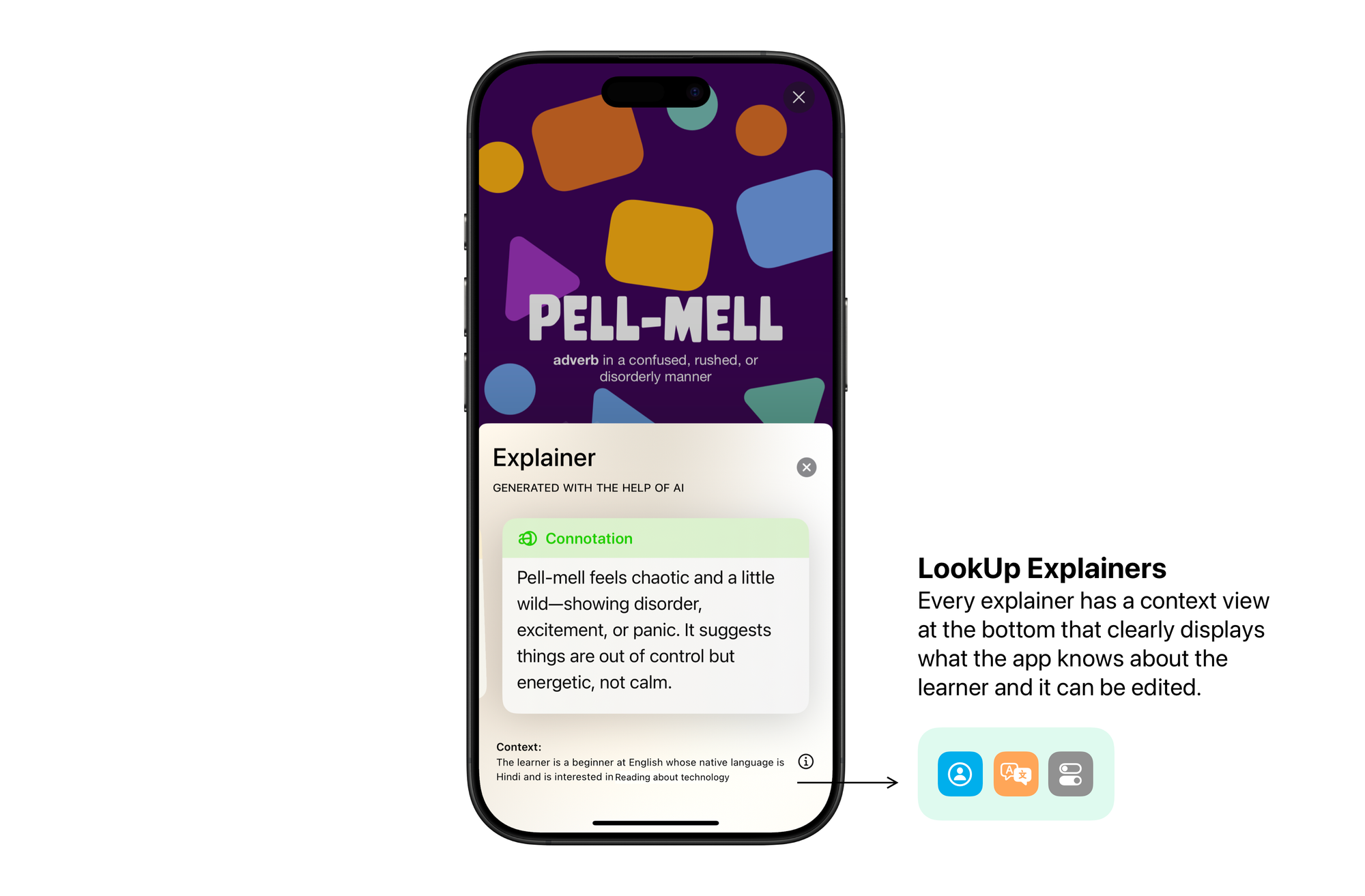

- Bound the context: Contextual understanding of a system is not infinite, it’s finite. Designers must do a good job of clearly showing the bounds of a system’s context.

- Be Clear: Clearly display what lead to a certain decision. This can mean showing what context a computer has on the user.

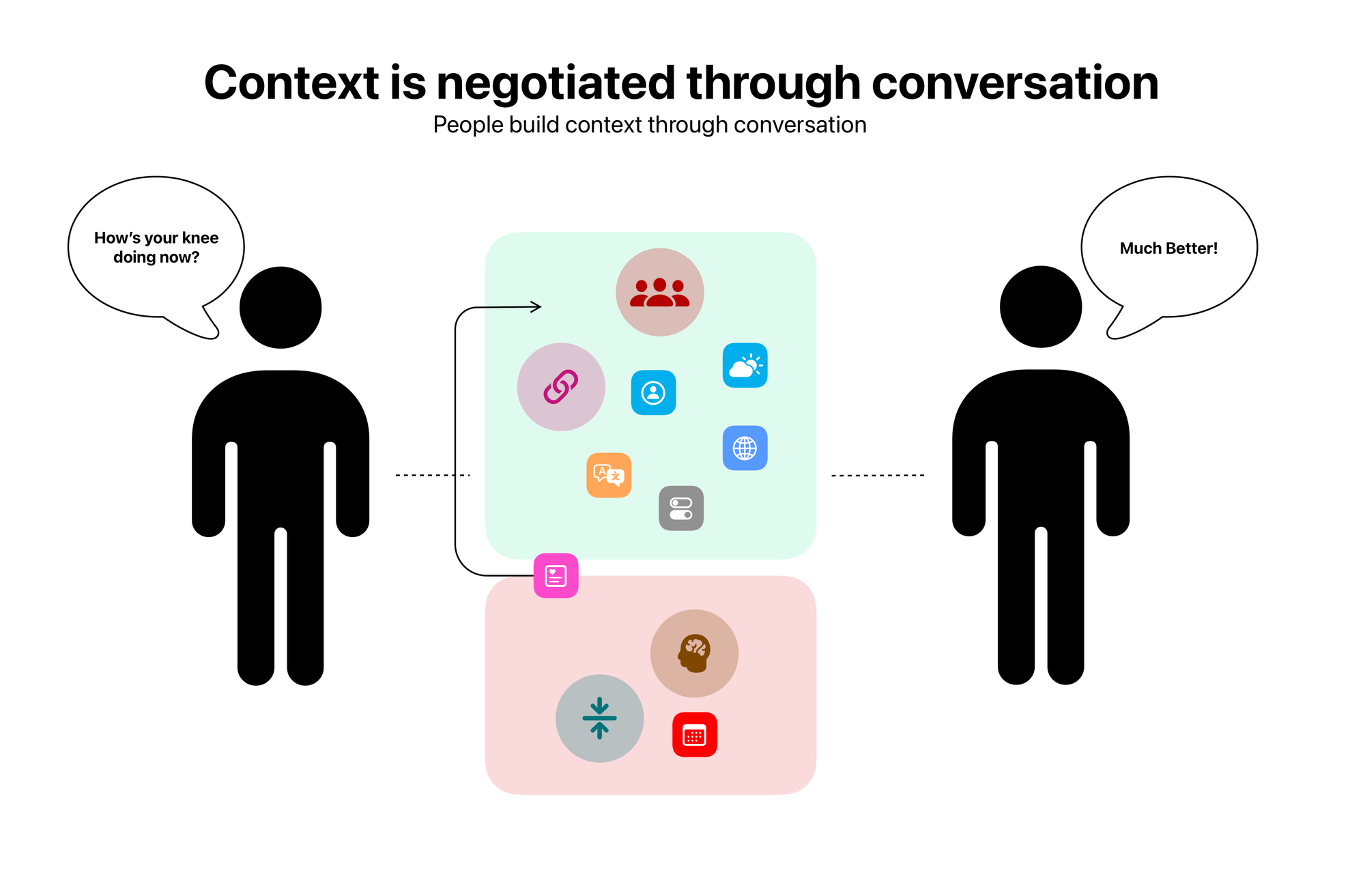

- Ask Follow-Ups: When there’s not enough context, ask people to get relevant information before proceeding. Also important to disambiguate when conflicts arise. (3)

Context isn’t static it’s a negotiation, between a person and the object they’re interacting with. Follow Ups and nudges make it easier to build an understanding of context. In our daily communication we constantly do this. Between our peers, we constantly negotiate context, by following up with questions. - Fail Gracefully: Everyone makes mistakes, computers do too. It’s important in those steps to provide clear pathways of resolving errors. Made an error, let people provide more context. Tell them it’s out of your knowledge bounds. Don’t make up information.

Finally, context as previously mentioned isn’t static. It’s dynamic and constantly being negotiated with the user. During the interaction process when the person clearly

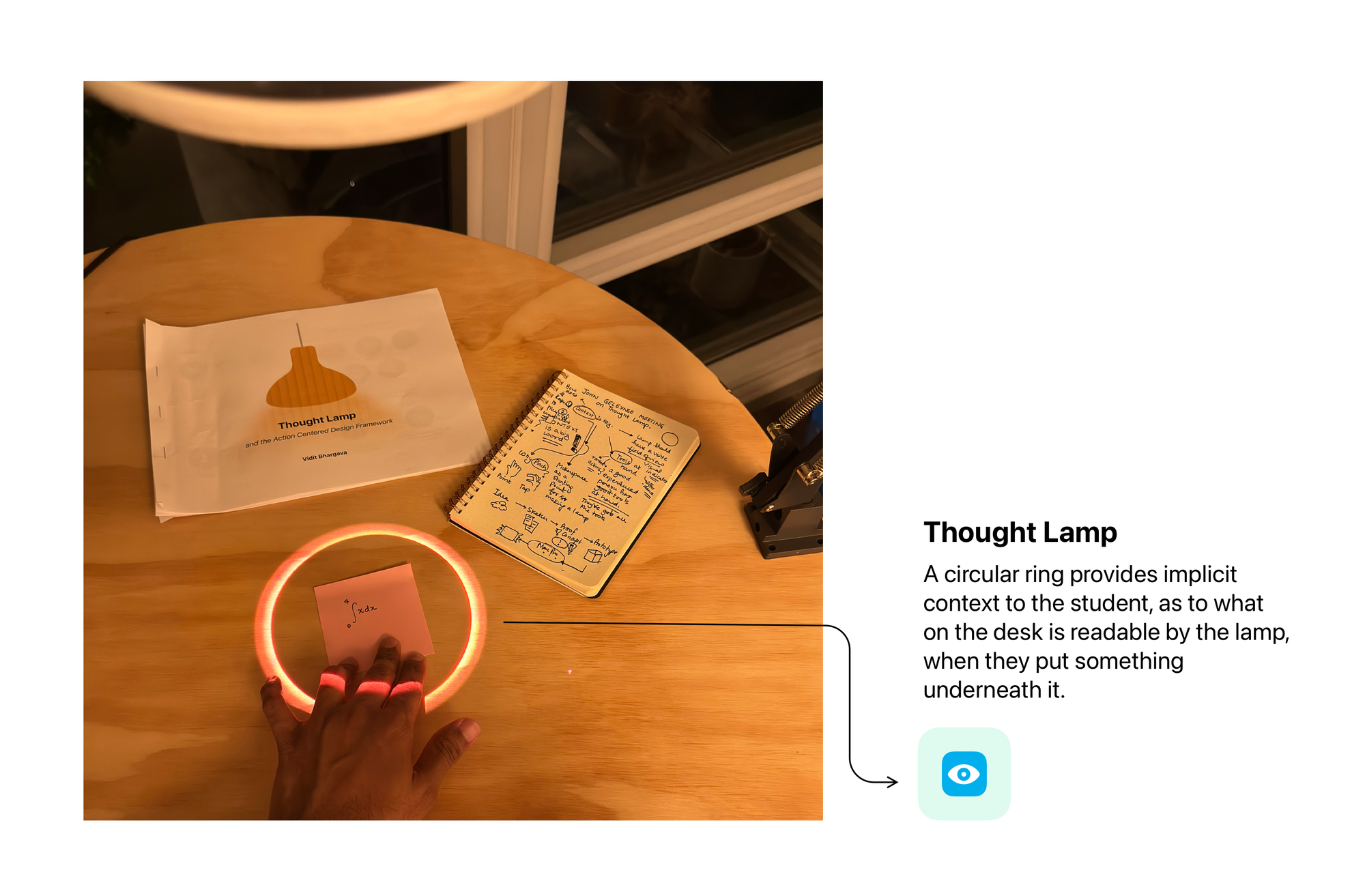

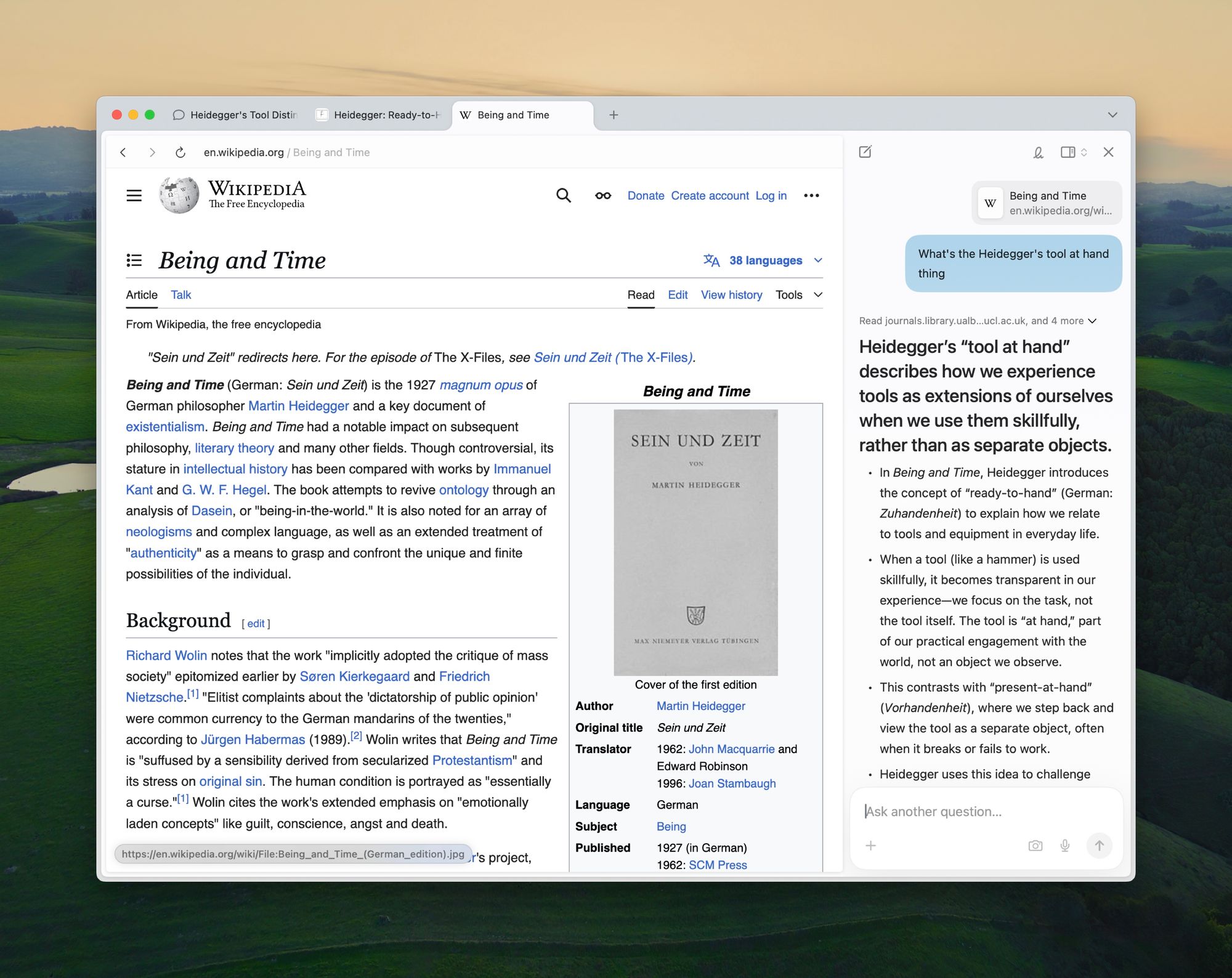

Some examples of Good Contextual Computing

Conclusion

Hoarding large amounts of personal data, serves other interests of tech companies but it doesn’t solve the problem of creating computing that understands its users so they can achieve their goals easily, without having to communicate with a computer in verbose terms. Context is a paradoxical and dynamic entity, that’s more than just raw data, it begins with the tangible and intangible relationships people have with their environment but goes far beyond that.

TLDR; Companies are never gonna get “full context” on a person, especially not by capturing large amounts of personal data. Any company serious about contextual computing should stop fooling around with the notion of complete context.

Contextual computing experiences don’t fail because there’s not enough context. They fail because there’s not enough shared understanding of context. If the person using the computer knows and understands what the computer knows about them to perform an action, or in design lingo, “the UI’s mental models match the user’s mental models” the experiences are better.

The answer to contextual-computing is not more context. It’s precise, limited and mutually understood context, it’s about getting affordances and mental models of a UI right.

Essential Readings

(1) What we talk about when we talk about context - Paul Dourish - 2004

https://cseweb.ucsd.edu/~goguen/courses/275/dourish.pdf

(2) Intelligibility and Accountability: Human Considerations in Context-Aware Systems -- Victoria Bellotti, Keith Edwards for Xerox Parc – 2001

https://faculty.cc.gatech.edu/~keith/pubs/hcij-context.pdf

(3) Boundary Objects — Star, Griesemer - 1989

https://courses.dubberly.com/design_theory_2017/04._a_Star_Griesemer_1989.pdf